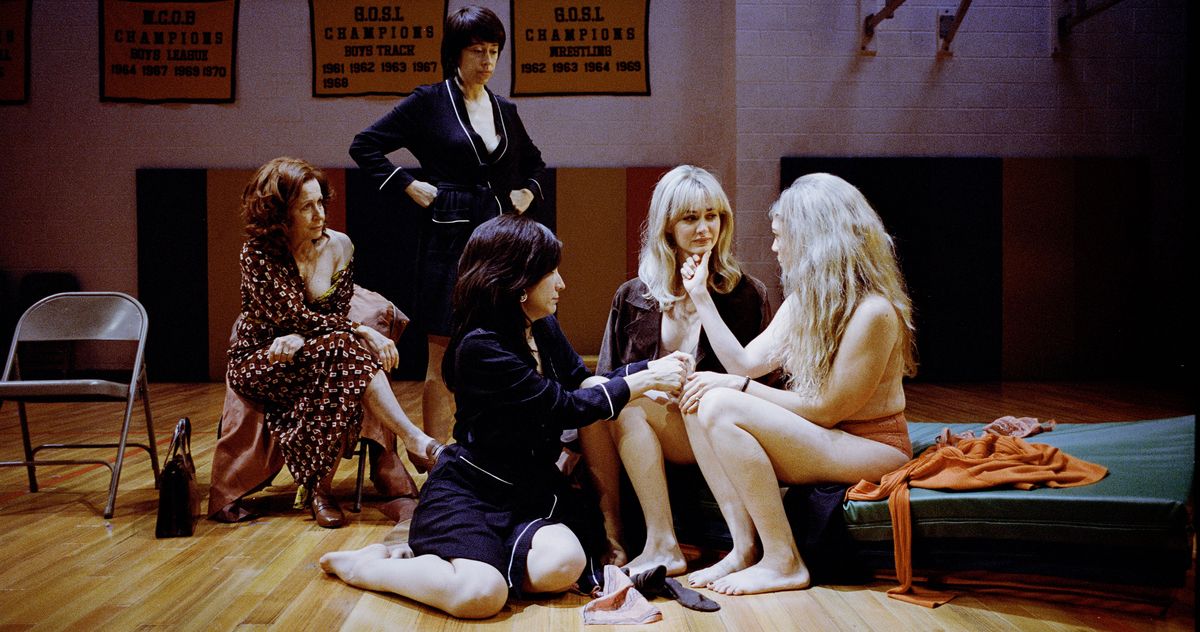

Betsy Aidem, Adina Verson, Irene Sofia Lucio, Audrey Corsa, and Susannah Flood rehearsing the opening scene of Act Two. Photo: Sara Messinger for New York Magazine

Causes for hope can feel dangerously scarce these days. In such a dire season of the spirit, it matters to hear from characters like the ones in Liberation, the extraordinary play by Bess Wohl transferring to Broadway in late October. Set in the 1970s at the meetings of a feminist consciousness-raising group — as well as in the present day, when a narrator (Susannah Flood) is telling the story of the group her mother founded — the show goes down like a bracing tonic, an antidote for the dark. It’s powered not by celebrities but by a company of superb New York theater regulars (the cast took home the Drama Desk Award for Best Ensemble) and engages in both exquisite character study and fervent political conversation — a thrilling dose of which occurs at the start of the second act during a pivotal 15-minute scene in which six cast members are entirely naked.

Like all of Liberation, the scene is funny, contemplative, and paper-cut sharp, a coup de théâtre for reasons beyond its state of undress. The show’s website discloses the nudity, and audience members are asked to put their phones in pouches during the performance, but even so, the actors tell me they’ve experienced a whole gamut of responses. “I remember this middle-aged woman was so scandalized,” says Audrey Corsa. “Guys,” says her castmate Irene Sofia Lucio, raising a practiced eyebrow, “we once heard the word titties!” Everyone groans. But, adds Flood, “the majority of people are swept up in the magic of what the scene accomplishes.” “Yes,” say several voices, one of them Betsy Aidem’s: “They don’t want someone to break the spell.”

What kind of work goes into building such a bold, prolonged, quite literally exposed sequence? To find out more, I’m sitting in on a rehearsal, and I’m not alone. My mother helped me wrestle the stroller off the subway — in it, my 4-month-old daughter is, for the moment, beatifically passed out.

Wohl had wanted to write a play about the feminist movement of the 1970s for what she calls “an embarrassingly long time, maybe 15 years.” Her mother, Lisa Cronin Wohl, worked there Ms. Magazine, and Wohl remembers going to the office with her and playing in “the tot lot.” Later, she’d go on marches with her mom and her mom’s friends. These women had been living in her head for years, but it wasn’t until she realized that she was trying to write more than a straightforward “historical play” that the project cracked open. “I didn’t even know I was writing a mother-daughter play for a while,” says Wohl. “It became a quest to understand my mom.”

Wohl’s drive as a playwright is to “put something onstage that I haven’t seen before.” For her, the image of multiple women “talking about their bodies and being naked but not being sexualized” — not “titillating or gratuitous” but compassionate and curious and rigorous — “felt a little bit radical.” It’s also historically accurate: Some feminist CR groups did indeed hold naked meetings, and Wohl — who interviewed around a dozen members of such groups while researching for the play — quickly discovered how meaningful the practice was. “It was something that the women talked about a lot and were very proud of,” she says. “This felt like a way that I could represent what they actually did — their bravery.”

Photo: Sara Messinger for New York Magazine

Susannah Flood, top and above, in rehearsal. Photo: Sara Messinger for New York Magazine

The show’s director, Whitney White (who earned a Tony nomination for Jaja’s African Hair Braiding, her Broadway debut), was aware that its nude scene would require real forethought. “I knew it would be something we’d have to dig deep for and get comfortable with and do the right way,” she says before adding wryly, “And full disclosure: I was an actor who had a horrible experience being nude onstage several times. So I often let that guide me. Like, Can you just do better than what you had?“When the show moved into rehearsal for its original Off Broadway run at Roundabout Theater Company earlier this year, White and her team filled the room with research material. She turned to Adam Curtis’s documentaries and Angela Davis’s writing as well as news clips from the era. “What is the average American digestion?” White asks. “You could look at high art and cinema all you want, but what’s the everyday? What was on ABC at the time?”

Such sensitive, granular world-building allowed the actors, says White, “to build real women that could be different” from themselves. “We really tried to make Venn diagrams: What is similar between the character of Susie and the actor playing her, and what’s radically different? From gender presentation to all kinds of things. That made the intimacy work feel depressurized.”

A caring — not to mention playful and deeply feminist — ethos suffuses Liberation‘s rehearsal room. Even the actors get underway with the big scene, you can feel it. They stretch and shake out their limbs and start to recite the dialogue while White asks questions and drops in reminders from the sidelines. Gradually, they move into more full-fledged scene work. “It is insane to me that my mother ever did this,” says Flood, as the narrator, breaking the scene’s fourth wall to address the audience.The never even saw her naked.”

No one, however, is naked right now. That’s not the point of this rehearsal and, according to the show’s team, it was very rare. “We work the text like hell, over and over, because that’s really more important,” White says. “I feel like the great challenge of the scene is to get the audience to remember that there is so much more going on, that the nudity is this tiny fraction.” I’m witnessing this rigor on its feet as White leans forward at certain moments while the actors work: “Clean that up,” she says. “Stay alive… Project it less; mean it more.”

Wohl’s characters are doing an exercise recommended by Ms. “The idea,” says Corsa’s Dora, who has brought in the magazine, “is we all go around and say one thing we love and one thing we hate about our bodies.” Kristolyn Lloyd’s Celeste, an uncompromising intellectual and the only Black woman in the group, is skeptical: “Frankly, I don’t exactly think we should be focusing on appearance at all.” But Lucio’s Isidora — an irresistibly uninhibited Sicilian filmmaker — is exuberant. “I Loven … my tits,” she says unapologetically. (“More Hamlet!” calls out White, and Lucio repeats the line with all the gravity of “To be, or not to be.” It kills.) Aidem’s Margie, the oldest in the group in her late 60s, cuts deep as she confesses that she hates her C-section scar, and Adina Verson’s Susie — a motorcycle-riding butch who writes brilliant punk manifestos on the backs of napkins — wins a big laugh every time she delivers the character’s laconic self-assessment: “Ass, good; tits, feh.”

To get to the moment of removing clothes on stage during the original production, the actors worked with intimacy director Kelsey Rainwater. As Corsa describes it, Rainwater acted “as a conduit to bring us all to a place where we felt comfortable knowing that we were all going to be at different levels of comfort.”

“She also sets rules and boundaries,” says Lloyd. “We don’t talk about our bodies. You don’t say anything you like or anything you don’t like.” “My character’s relationship to their body and my relationship to my body are quite different,” says Lucio. “Finding a way to bridge that, and to almost have Isidora’s body be a costume, has been really, really helpful.” She pauses, then grins slyly: “Some of us wear merkins in the show as well, which for me added another layer of This is a flesh costume for me.“There are a few hoots and hollers as the others agree or protest.”The did not want a merkin,” says Lloyd, drawing herself up with Miss Jean Brodie rectitude as her fellow actors cackle. “I’m perfectly capable of growing my own.”

Audrey Corsa, left, in rehearsal. Photo: Sara Messinger for New York Magazine

Once the scene had been thoroughly rehearsed, the actors switched from doing it fully clothed to attempting it in underwear or camisoles provided by the show’s designers. Team members put up curtains around the room and dimmed the lights, and, says Aidem, “they had anybody male leave the room when we did it the first time in our underwear.” Then, says Verson, “a few times later, we wondered, ‘Are we ready to do it topless?’” For Verson, the tempo eventually started to chafe a little: “It was like, Let’s just fucking do it! But Lloyd pushes back: “Being an other in this group and having the only chocolate nipples onstage, I needed the slowness.”

Still, the actors are passionately united when it comes to the scene’s importance. “We might be providing the audience an opportunity to overcome their discomfort with naked bodies, period — but especially naked female bodies,” says Flood. “And the fact that we’re on Broadway now, we’re saying that this kind of a discussion is commercially viable.” Verson nods in excitement: “I wish when I was a teenager, I could have seen regular bodies onstage. Like, look at all the different labia! Seriously, look at all the different mons pubises! They’re all normal.”

There’s another world where this cast takes the Broadway stage, at whatever level of dress, under America’s first woman president — another timeline in which Liberationmight have felt, says Wohl ruefully, like “a celebratory play about how far we’ve come.” Instead, the show has become a vessel for both deep pain and lasting, unkillable hope. “Back in March when we did it,” Wohl remembers, “people were really coming into the theater with a need to be together in this moment and collectively understand what was happening. Which was also the protagonist’s search: How did this happen? How did we get here? What went wrong? “She takes a breath. “It’s funny. I didn’t know, when we went back into rehearsals this time, how it would feel. Are the questions going to feel as urgent? Are they going to feel different? Are we more tired now? Are we more angry now? Where are we as a society? And I feel, actually, that so far the questions are still the same. They’ve just deepened in certain ways, and there’s a rawness to them. I guess we’re both more tired and it feels more urgent at the same time. It all turned out to be true.”

As my mother and I return home, I look at my daughter’s face. She’s sleeping again. “You know,” my mom says, “in college, my friend Beth was incensed that only the men had a sauna in the gym locker rooms. So one day we all just took off our clothes and marched through the men’s locker room in our towels to liberate the sauna. We were naked and all these big naked football players kept opening the door and — !” She makes a horrified face and laughs. I laugh too, and also I’m in awe. I never knew this until now.

Source link

اترك تعليقاً