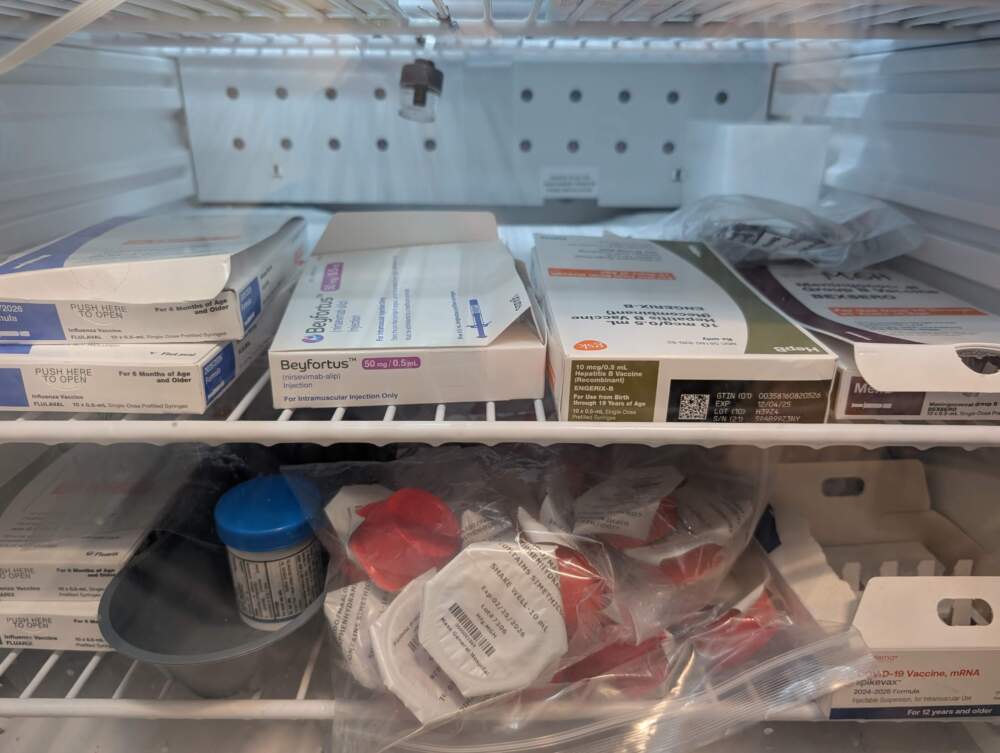

On any given day, nurses at the Massachusetts General Hospital pediatric clinic in Chelsea administer dozens of vaccines — shots that protect children from measles, polio, hepatitis, flu and other diseases.

These vaccines have been a cornerstone of medical care for decades. But what used to be routine is increasingly becoming controversial.

Pediatricians and public health officials say a growing number of Massachusetts families are questioning and rejecting vaccines. This raises the risk that diseases will spread. And it means doctors working in community clinics like this one are exerting more time and energy debunking misinformation and urging parents to get their kids immunized.

Vaccine skepticism has been swelling in recent years, fueled by distrust of public health guidance that grew during the COVID-19 pandemic and an increase in misinformation circulating online.

Myths about vaccines now have a prominent platform under President Trump’s administration. Trump’s health secretary, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., has linked childhood vaccines to autism, although scientists have repeatedly found the two are unrelated. And the president himself has questioned vaccine safety.

Dr. Alexy Arauz Boudreau, who works at the Chelsea clinic, said almost every one of her patients had all their vaccines up until a few years ago. But now, she estimates more than 10% are unvaccinated.

And Arauz Boudreau, division chief of primary care pediatrics at Mass. General, said she’s seen an “exponential” rise in skepticism this year, after the change of administration in Washington.

“The safety and effectiveness of true proven preventive measures is being questioned on all fronts,” she said.

Pediatricians across Greater Boston said they are extending patient visits and booking follow-up appointments to talk to families about vaccines. That means less time to talk about other important topics like sleep and nutrition.

“My hope is that we’re strengthening dialogue, as opposed to shutting down dialogue,” Arauz Boudreau said. Still, sometimes parents will “absolutely refuse to even hear a potential explanation. That’s when I worry. We can all disagree, but let’s have a conversation.”

Experts who study vaccines emphasize there is overwhelming evidence that vaccines are safe and work well for the vast majority of people. They say side effects like pain, fever and fatigue are temporary and are far outweighed by the protection vaccines offer against serious diseases.

Arauz Boudreau said it’s painful to see new doubts raised about vaccines that have been studied and refined over many years.

“Why would we put our nation’s children’s health on the line?” she said. “They’re innocent, and really are trusting us as the adults in their world to make sound decisions for their well-being.”

About 16% of American parents have delayed or skipped at least one vaccine for their children, counting the flu and COVID shots, according to a KFF/Washington Post survey. Among Republicans who identify with Trump’s Make America Great Again movement, the figure is even higher: 25%.

Medical experts say very contagious diseases like measles — which is currently spreading in parts of the United States — require vaccination levels over 95% to stem transmission in the community.

Massachusetts has among the highest vaccination rates in the country, but even here, the numbers are falling, according to state health officials.

Students in Massachusetts schools are required to be vaccinated against several diseases, including measles, chickenpox, polio and whooping cough. But parents can opt out for medical or religious reasons.

Department of Public Health data show the share of kindergartners whose parents requested and received exemptions from vaccine requirements has increased since the pandemic, from just over 1% of students receiving exemptions in 2021 to nearly 1.5% in 2024. (This year’s numbers are not yet final.) Vaccination rates are highest in and around Boston, and lowest in rural parts of the state.

Dr. Brenda Anders Pring, president of the Massachusetts Chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics, said this is new territory for many of her colleagues, who are still figuring out how to talk to skeptical patients.

“The language we may have learned 10 years ago is very different from the language that may resonate now,” Pring said.

Pring, who sees patients in Boston, said she gets a variety of questions from parents about why vaccines are necessary and how the shots will make their babies feel.

She stayed late at work on a recent Friday night because a family with a newborn baby was hesitant to get the hepatitis B vaccine, which protects against severe liver disease. The parents said they didn’t know what the vaccine was made of, so Pring found them a list of ingredients.

“I got home pretty late,” Pring said. “But I was like, ‘I’m doing this for this baby.’ “

Even with that extra effort, the parents still decided not to give their infant the vaccine that day.

Among parents who are passing on vaccines, some say they don’t trust the science. Others are squeamish about seeing their infants cry, even temporarily, when pricked with a needle. And some say they’re confused by the mixed messages coming from different sources — their doctors, the White House, social media and more.

There are also parents on the other end of the spectrum. Karla Haney, a mother of two from Malden, asked for her 9-month-old daughter, Elena, to receive the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine a few months early because the family was about to travel overseas and could be exposed to more germs.

“I believe the data, and I believe in the protection that it offers,” said Haney, who works as a critical care nurse.

The vaccine schedule long used by pediatricians and recommended by public health officials calls for children to start receiving vaccines as soon as they’re born, followed by shots at 2 months, 4 months and several other times during their first years of life.

Sometimes, parents ask to space out the vaccines. Pediatricians don’t recommend this strategy because it requires families to come back to the office more often for shots. But it’s better than skipping vaccines altogether, they say.

Dr. Nisha Thakrar, chief medical officer at South Boston Community Health Center, said she sometimes schedules telehealth appointments just to talk with parents who have lots of questions about vaccines.

She often tells them: “I vaccinated my kids, and my goal is to give your kids as good care as I gave my kids.”

Some medical practices do not allow unvaccinated patients. Thakrar, a pediatrician, said she wants to keep seeing these families, because every visit is another opportunity to talk about the benefits of vaccines.

Doctors, she said, “don’t want to feel like the enemy. We want to be the partner in raising people’s children.”

اترك تعليقاً