SPOILER ALERT: This interview contains major details for Sorry, Baby.

Despite the film’s heartbreaking subject matter, Eva Victor is all smiles during our interview. Sorry, Baby, written and directed by Victor, who also stars, is a dark dramedy that centers around Agnes (Victor), a college professor who struggles to cope with the aftermath of a sexual assault that took place three years ago on the campus she teaches at when she was a grad student. Trying her best to roll with life’s continued punches, Agnes finds comfort in the little things, such as adopting a stray cat, sparking up a romance with her neighbor Gavin (Lucas Hedges) and eating delicious sandwiches with strangers. But what really keeps Agnes afloat when the world seems to move on without her is the enduring relationship with her best friend, Lydie (Naomi Ackie), who drops the news that she’s expecting, prompting Agnes to prematurely spiral about the potential shift in their friendship. To say the least, the film is an emotionally resonant and complex showcase that unabashedly shows Agnes’ imperfect journey through the other side of trauma.

Now that the film has released to streaming on HBO Max, how does Victor envision the story’s reception with a larger audience online? “I’m really happy that now people get to watch the movie in their bed with their cat,” the filmmaker says. “My directive to people would be, now you can curl up, it’s not at the movie theater, so the pressure is off. Just turn on the movie, bring your best friend, bring a snack and let’s lock in.” Since the film’s critically praised debut at the Sundance Film Festival earlier this year, Sorry, Baby has also garnered two nominations for Best Feature and Best Original Screenplay at the Gotham Awards.

Below, Deadline speaks to Victor about their directorial debut, building a loving friendship and getting through the unspeakable hardships that life can throw at you.

DEADLINE: This story is loosely based on something that happened in your life?

EVA VICTOR: It’s a very personal story. I’ll say that.

DEADLINE: How did you manage to give up these vulnerable parts of yourself to tell this story? Because it’s incredibly visceral. How did you get to a place where you felt comfortable putting this out into the world?

VICTOR: A lot of the film was so vulnerable because when I was writing it, I never thought the film would get made when I was making it. So, I didn’t really consider what it was like to premiere a film or how exposing it would be. So much of my experience was based on wanting to make the most truthful film possible. I wasn’t really aware or concerned with what would happen afterward, which has been really interesting because I think in order to write the film, that was very much an experience of wanting to process something, and also wanting only to write it once I had enough distance from the experience to see it in the most empathetic way possible towards myself.

I feel like there was a lot of work to do to figure out how to find empathy for this character, who isn’t me but is built around me. And that took time to figure out how to tell the story as efficiently as possible, and I think, honestly, the story itself came from a desire to see something on screen and to feel something when I was watching something on screen that I couldn’t find. And that was really about wanting to talk about the aftermath of something and not finding a film about that, but instead finding films about violence, which are totally valid. I just couldn’t find the specific thing I wanted. So much of life after trauma is about processing healing, which is a lifelong thing. There’s really no destination. There are milestones, but it’s not like you land and then forget that nothing was ever done.

But the film is also about a very life-saving friendship, and I was lucky enough to have that support from a friend, and a great motivator for making the film as truthfully as possible. It was great to honor that friend and to make the film feel like a love letter to friendship and a friend’s love, trust and help.

DEADLINE: Has it been an adjustment for your career, considering that before this, you were mostly known for your funny videos online? Now you’re known for this very serious, poignant story.

VICTOR: Yeah, when you’re a person making videos on Twitter, no one wants you to make a movie. It’s just not what they ask of you. They want something different. And it took me writing the scripts to be like, “This is what I want to make.” The scripts kind of had to speak for that transition for me. The script had to be strong enough. I had to have a vision of what I wanted to do and understand what I wanted to do. It’s a really weird thing to have those quirky online videos that people saw of me lead me to having some seriously real jobs. I was on a TV show because of it, and got to be on set in a professional way for the first time because of it. And that taught me so much about sets, what a collaboration looks like and building a character.

Also, I think when you want to make a big transition in how people see you, you kind of have to bang the door down and make something, and it kind of felt like the task was right, something that had to be made that was perceived as undeniable so that the script forced them to take me seriously versus asking for it and then writing it. You know what I mean? No one is going to say yes to an idea; they’re going to say yes to the thing that exists. So (getting the script together) felt like the task at hand to get people to jump with me.

DEADLINE: Was there a scene that resonated with you after seeing the completed film that, perhaps, while filming, you didn’t think would translate well on screen?

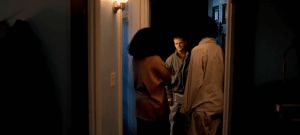

VICTOR: There were many things. I was really convinced that I wanted the drive home after Agnes goes into the professor’s house, including the walk back to the car and drive home, to be one shot. We could only be at that location for one night, and it included everything outside the professor’s house, outside the school, and the drive home. We did end up getting it, but every time (we filmed) there was something I didn’t like about it. Then I got to the edit and realized that’s one of the parts that I think functions the most efficiently in the film. There are other things I was convinced I would die holding onto in the film that aren’t there. But that’s the beauty of the edit: it becomes its own. The film starts to speak for itself, and you just have to humble yourself to it and say, “This was my best guess of what I thought the film needed and that was wrong.”

DEADLINE: In talking more about omissions, you don’t show the assault, just the aftermath. Which I think is a more powerful approach, as the audience has to grapple with the silence of Agnes’ walk to her car and her drive home.

VICTOR: There was a big debate about that part where a kid tells Agnes that her shoes are untied. In the script, she responded, “Thanks.” But we cut that. A lot of people watching it were like, “Why does he say that?” And most of the women in the audience were like, “Yeah, guys are always telling you your shoes are untied, when you obviously know.” No one doesn’t know that their shoes are untied. And, I was like, “That’s a good enough reason to keep it in.” People are really living in different worlds.

DEADLINE: Agnes also makes the decision not to track her attacker down or be more aggressive in her pursuit to see that he is arrested for his crime. We don’t even see the professor again in the film after the assault. Why were these things important for the story you wanted to tell?

VICTOR: The film is so not about him, which I really like. I wrote the film with the intention to never go inside the house. The absence of that scene was a huge motivator for making the film because I really wanted to prove to myself that a film doesn’t have to put its audience through that kind of violence in order to be emotionally moving. My question was: is it possible to put one into a subjective experience by not showing it more than if you did show it? Because my question was, does an audience member’s body, depending on what they’ve been through, shut down upon seeing a scene like that and then not be open to the film? Is there a way for the film to hold an audience member through the violence instead of shocking them with it, and to meet them on the other side with an open heart? So that was the reason I wanted that to be there. That was the morality of it for me.

And beyond that, I think it mattered to me that we hear what happened to Agnes on her own terms. When she’s ready to say it, when she’s feeling safe, we don’t know what happened to her before she knows, because that felt cruel. It felt condescending to be like, “We know this happened, and we’re just waiting for you to catch up.” I never wanted the film to be ahead of her in that way. I also think of it as Agnes’ body going into that house, but her spirit doesn’t. There’s something about staying outside the house, for me, that feels apt in conversation with the trauma response of freezing, and potentially her memory of that experience could be just that frame. So that’s why it was important for me to do that. Then, how we shot the whole walk and drive home was meant to give her some privacy. The darkness was about not showing her face as she’s processing, we only see her face until she’s in the safety of Lydie’s company.

Agnes does what she feels is right to her (in handling this experience). The first thing she does is go to the doctor, which is a really difficult, demoralizing and devastating experience. She does report it, but the school is not helpful, and she’s met with some gaslighting and cruelty. What’s so demoralizing is that she thinks of that idea for justice for one 20-minute period, burning his office down, and then she quickly realizes that that’s not what justice is.

I wasn’t interested in telling a legal story. I was much more interested in sharing the part of the experience that feels so unjust and so lonely, and in connecting with the emotionality of days bleeding into each other, and in how time moves very slowly after a trauma when everyone else moves on. This wasn’t meant to be a procedural thing where she’s looking for justice through the legal system, because the legal system has always failed people who’ve been through this kind of thing. There’s a line where she says, “I don’t want him to go to jail because he’d just be someone who goes to jail who does that. I want him to stop being someone who does that.” And I really believe that.

I’ve always felt like rehabilitation would be the most comforting justice possible in this situation, and that’s not what we’re set up to provide people with. So, I felt like the legal system failing, and then not being a big part of the story felt more true to reality.

DEADLINE: The friendship dynamic between Agnes and Lydie feels so lived in. Talk more about their partnership and working with Naomi Ackie.

VICTOR: I do think I was completely head over heels for Naomi the entire time we were filming. I just couldn’t handle her. I thought she was so fucking good and so thoughtful, and she really radiates this psychotically powerful energy of warmth, and she’s a brilliant actress. She’s so effortlessly brilliant, open, and vulnerable, and I think so much of our work together was just about enjoying each other’s company. It was really cool to be working with the different actors for different roles in the film because everybody’s process and what they needed to do felt (so engaging). With Naomi and me, it was so effortless the first time we met. We were just like, “We’re going to build the first week of us doing friendship scenes so we could just hang out all day on camera.” It was very fun. Lucas (Hedges), on the other hand, he wanted to rehearse a ton, and that was cool because I felt like I got a masterclass with all these brilliant actors.

For the character of Lydie, I was really excited to have this really exciting queer journey that feels like from the first time we meet her, she’s not even aware of her queerness, and then by the end of the film, she has this family and this baby. She’s living in New York, writing a book. She’s totally come into her own. I feel like that was a really exciting thing to give her, sort of this joyful explosion of understanding herself, but also putting that up against Agnes, who, in the last five years, has moved a table in her house to the other side of the room —that’s Agnes’ growth. Putting someone with a huge awakening next to someone who’s just trying to make it through the day is very helpful for the storytelling of time moving in different ways for different people. It was exciting to let Liddy live her life outside of Agnes, because there’s so much caretaking and worry she has for Agnes. Then I think the reason their friendship for me probably lasts a lifetime is because she prioritized herself and went to New York, even though Agnes stayed around and is stuck.

But Lydie gives Agnes this huge gift of listening, of holding her and of not being afraid of what she’s saying. The journey of the film is meant to show Agnes having a glimpse of what it’s like to feel she could do that for someone else, and that’s for the baby at the end. So, for Lydie, it’s obviously the main relationship of the film, and it was always meant to be this love letter to a friendship that’s so close and romantic.

DEADLINE: Let’s also talk about Agnes’ sexuality. Agnes has Gavin as a sexual partner, but there’s that scene in the courtroom where Agnes doesn’t really subscribe to a gender when filling out the jury summons. You also go by she/they pronouns, so I’m curious about the intentions behind this all.

VICTOR: Look, by the time you make a movie, after five years of starting to write a movie, nothing is random. Agnes goes through this experience and trauma that makes you question all these rules about the world. Such as the rules you’re presented that are like, “Oh yeah, that’s your body and no one can touch it without your permission.” And there’s girls and there’s boys and I think after you have the kind of mind-bending experience of someone betraying one of the fundamental rules that’s meant to keep you safe, it honestly has you question other rules that maybe don’t serve you and I think Agnes is having an experience of trying to rebuild her body from scratch and get in touch with it after dissociating out of it. I think when she’s coming back into her body, she’s forced to look at a paper that says, “Are you a girl or are you a boy?” And Agnes is like, “Well, why are there only two bubbles? That’s not my experience of my body and of my life.” And so, she creates her own experience of that.

A character introduced at the end is Lydie’s partner Fran (E. R. Fightmaster), the character and the actor are non-binary. I really wanted Fran to feel like a mirror for Agnes, showing who Agnes could be, and that’s why Agnes is so mad at them all the time. Agnes can’t really look at them because they are this sort of outward expression of where Agnes wishes that she was. So, Agnes is very much on a journey with gender and it’s interesting.

It’s an interesting experience to put that, blatantly so, in a film for people to see. It’s also been an interesting experience of doing press and using they/she pronouns and being put onto lists where I’m called a woman or the friendship is discussed as female friendship—which I get because this is that kind of intoxicating quality of women together and Agnes kind of pronounces in the film that she’s not feeling like that. But it’s interesting to experience how people find it essential to box me up, when the fluidity of it is what’s very comforting to me, and what feels exciting to me is being able to be two things and a million things at once. It’s not necessarily a conversation; it’s the nuance of that.

DEADLINE: Lastly, I have to ask about the titular Baby. Agnes unloads the weight of the world on the baby by explaining that some bad life experiences are going to happen, but at least the baby has a good support system. Why was it important to frame the structure of the movie around the baby at the end?

VICTOR: The film is about a friendship — so the structure of the film is informed by the journey of that relationship. The beginning of the film is Lydie arriving and warming up Agnes’ life up with a visit, she tells Agnes big news about a baby coming. Agnes doesn’t handle this news elegantly; she responds rather selfishly, with “Are you gonna name it Agnes?” The middle of the film is marked by this generous, loving moment where Agnes tells Lydie what happened to her, and Lydie listens, and holds that without trying to fix it. At the end, Lydie visits Agnes with the manifestation of the news Agnes received at the beginning of the film— the baby is finally here. Time has passed. And, for the first time in a while, Agnes sees Lydie’s needs outside of her own— she sees Lydie wants to go on a walk with her partner Fran, so Agnes offers to babysit, which is a much more elegant response than “Are you gonna name it Agnes”. And even though it’s a small offering, it marks the end of Agnes not being able to see outside herself. And when she sits with the baby, which she feels, at first, a bit of jealousy towards by saying. “I’m no longer the baby, there’s a baby now,” she’s able to feel of use.

She vows to the baby to be there to listen and to not be scared, like Lydie did for her. By listening and not being scared, Lydie saved Agnes’ life. And Agnes now understands that she is capable of doing that too. The end of the film marks, to me, the end of a particular chapter of healing. Nothing is healed fully; it probably never will be. But it marks the end of these years of feeling without use. It was always the ending of the film. It’s what the whole film is building towards energetically to me.

Sorry, Baby is now streaming on HBO Max.

(This interview has been edited for length and clarity)

Source link

اترك تعليقاً