This is the third story in a three-part series on Boston artist Allan Rohan Crite. Read the first story here and the second story here.

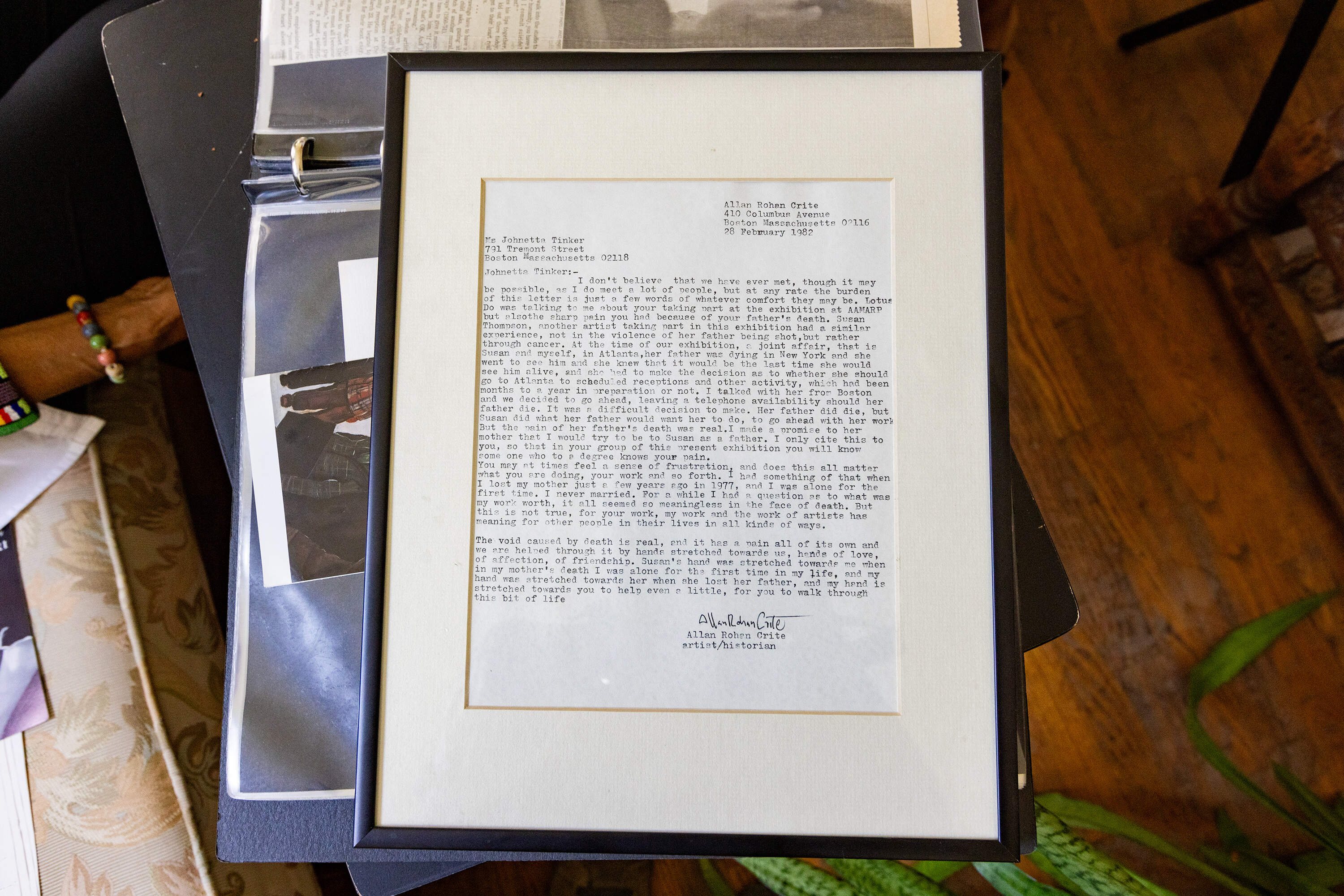

When artist Johnetta Tinker lost her father in the early 1980s, she was on the verge of pulling out of an exhibition. Then, she received a handwritten letter from Allan Rohan Crite. She’d heard of the famous artist but had never met him in person.

“The void caused by death is real and it has a pain all of its own and we are helped through it by hands stretched towards us,” Tinker read from the letter. “And my hand is stretched towards you, even if it’s to help you walk through this bit of life.”

This letter convinced Tinker to stay in the exhibition. “And then he invited me over to his studio,” she said. “He said to me, ‘Well, you lost your father, but if you want a father, I’ll be your father. I’m everybody’s father.’ And he really was.”

In many ways, Tinker’s experience meeting Crite exemplifies what defines him as a person and mentor. Crite became known in Boston as the dean of Black artists because he showed up to so many exhibitions and shows, usually with his signature sketchbook in hand. Mentees recall him constantly recommending other artists for fellowships and opportunities. Textile artist Susan Thompson experienced this in her decades-long friendship with Crite.

“Wherever he would go to support people, he would take me with him and he introduced me as this amazing artist,” Thompson said. “And because he said I was amazing, people believed him.”

Crite’s mother, whom he lived with his entire life, passed away in 1977. He described feeling lonely after her death in his letter to Johnetta Tinker. But through his constant appearances at local shows and exhibitions, Crite met many young Black artists, including Napoleon Jones-Henderson and Aukram Burton, that he formed lifelong friendships with.

“While I don’t have a biological family, I do have a family in another sense,” Crite said in a 1979 oral interview with the Smithsonian Institute.

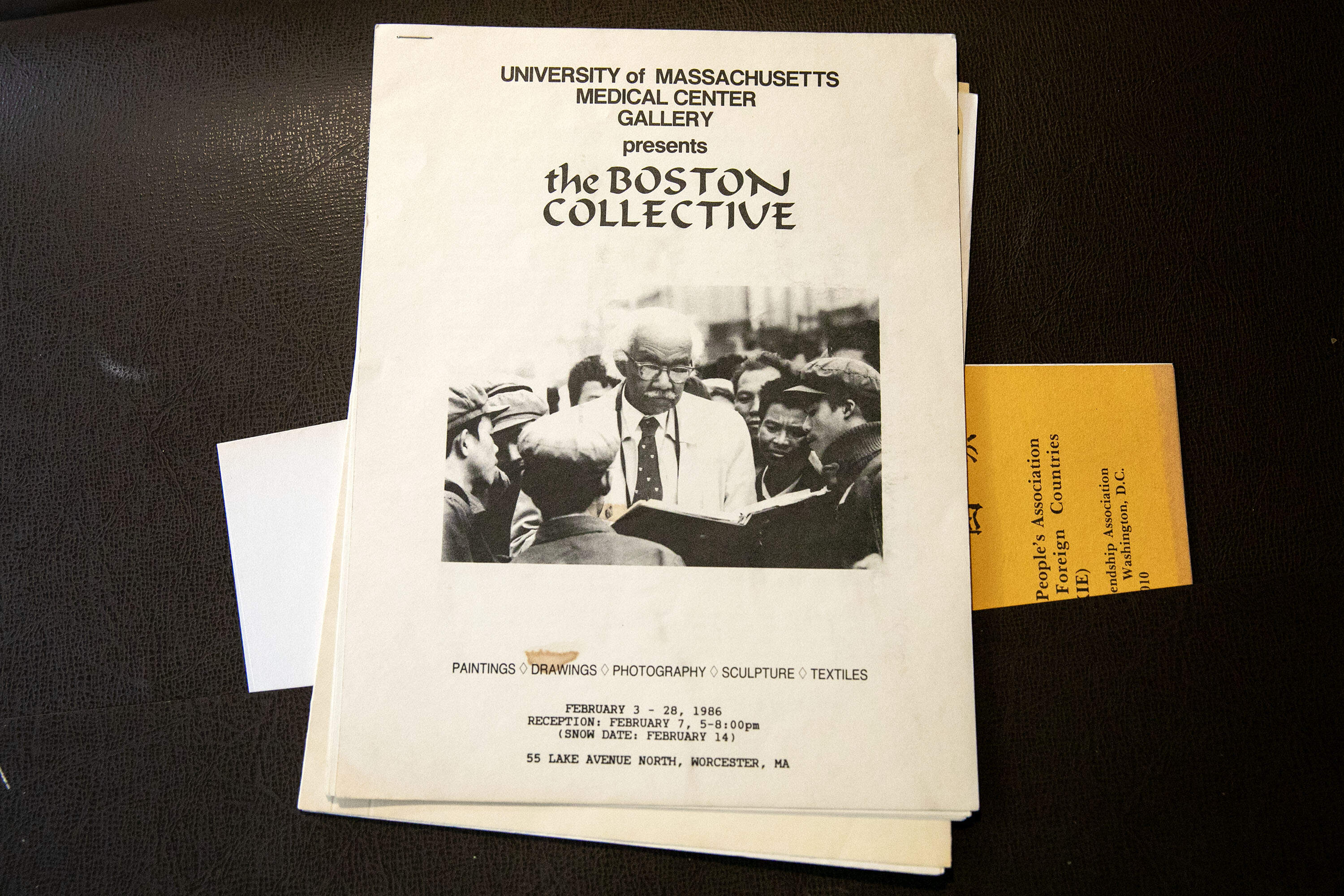

Some of the artists Crite met, including Burton, Thompson, Tinker and Jones-Henderson, would go on to form the Boston Collective in the late 1970s. The group supported each other and exhibited artwork together in Boston and beyond. While Crite didn’t start the collective, he soon became a major fixture in the group.

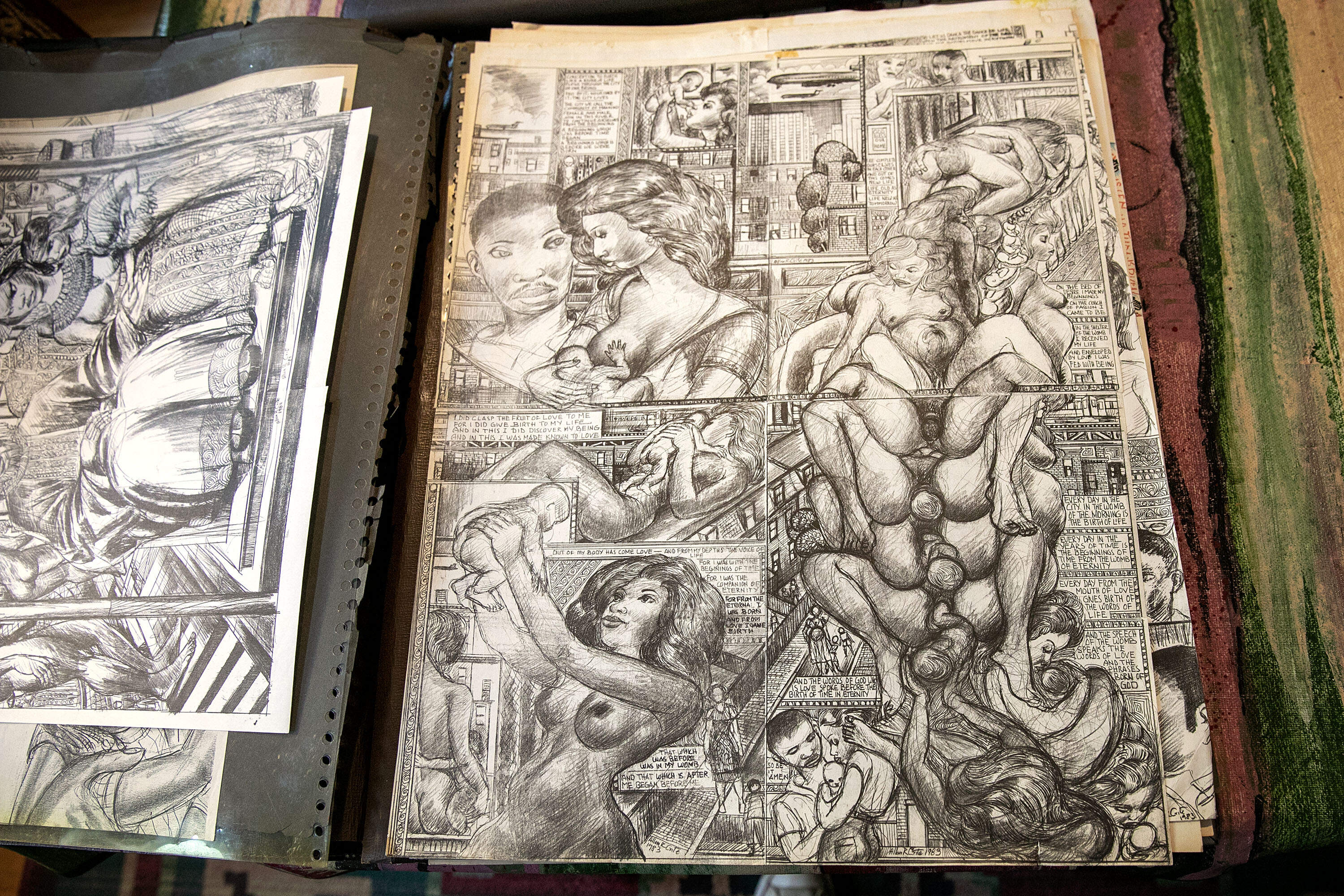

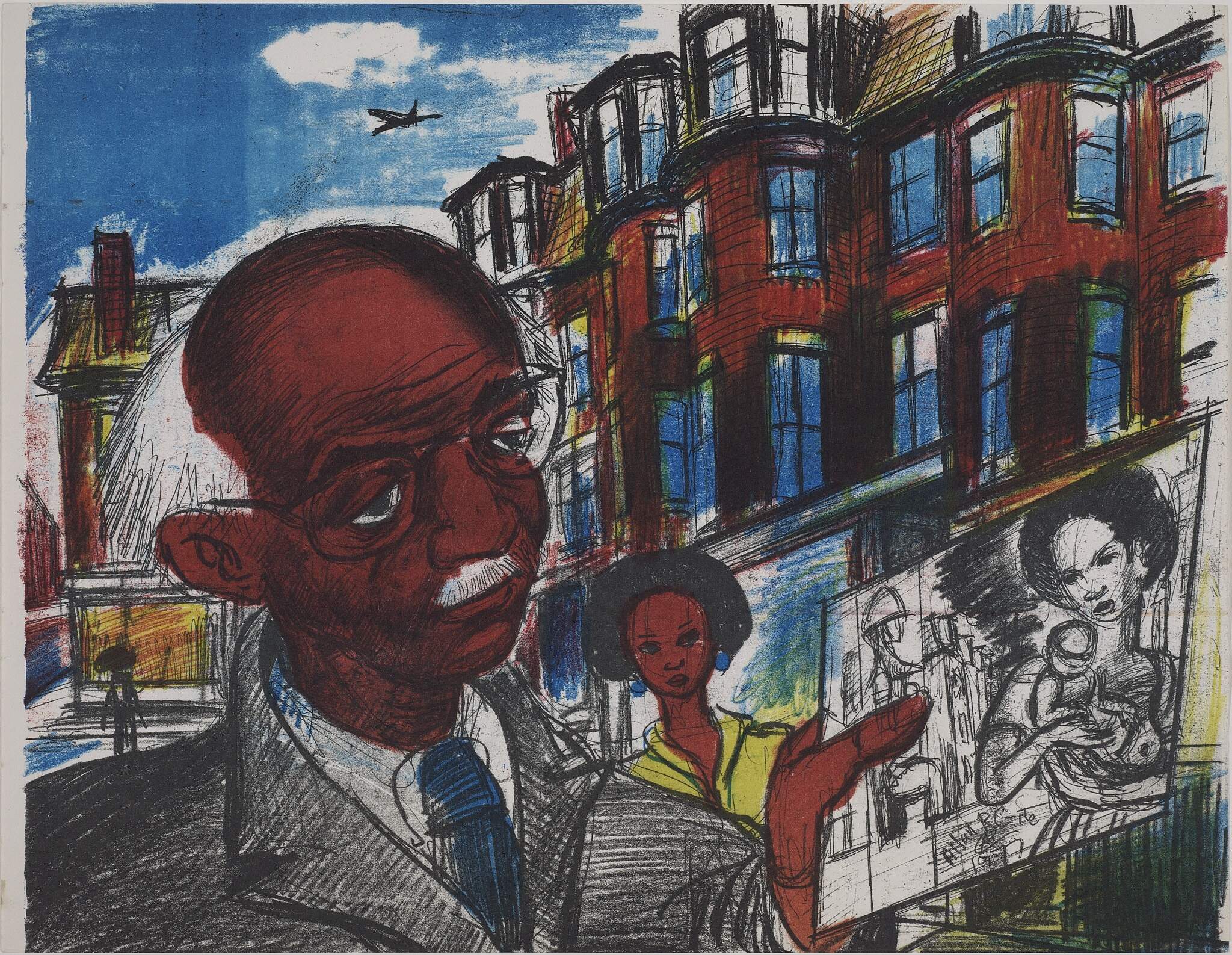

“Aukram (Burton) put together a proposal for us to do another trip to China. We had an exhibition in Guangzhou,” Thompson recalled. “It was a cultural exchange.” The collective shared more about Black culture and their art during their visit. Crite documented the 1983 trip in a series of drawings that resemble a graphic novel, a style he was experimenting with in the latter years of his career.

Back in Boston, Crite’s commitment to fostering community went beyond his involvement with the Collective. His home at 410 Columbus Ave. became a vibrant hub for artists, friends, and mentees.

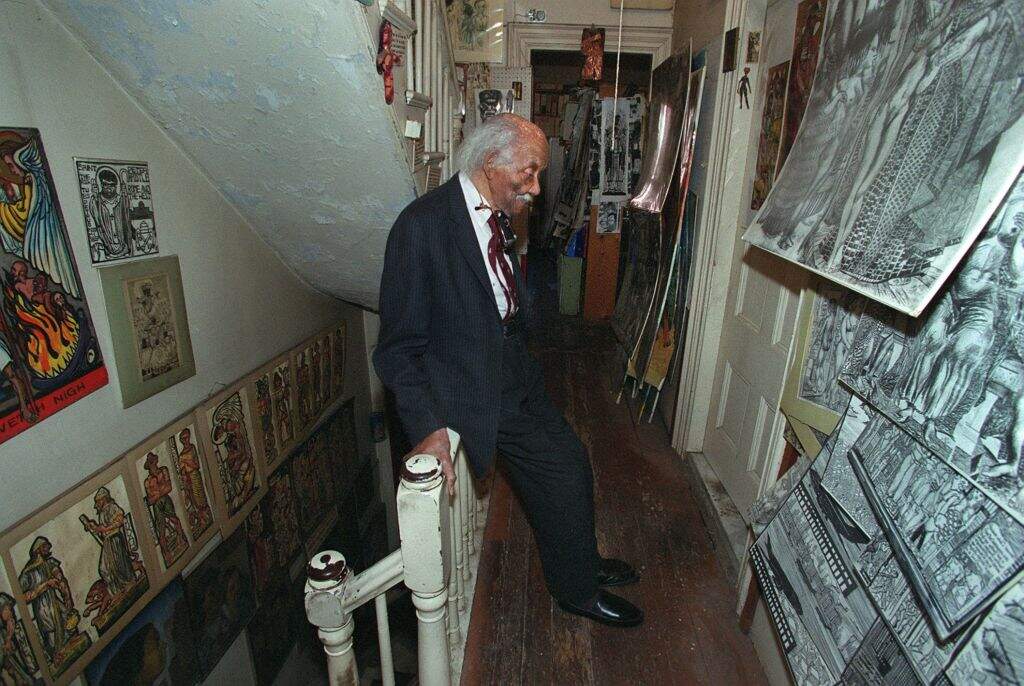

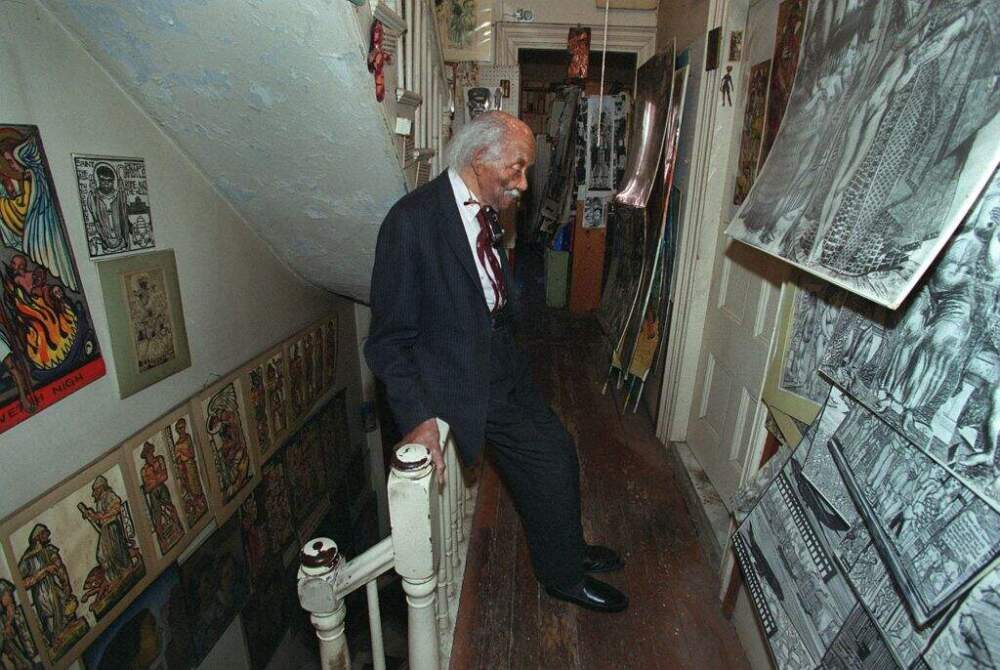

After his mother’s death, Crite lived alone in the South End. When he met Thompson, he offered her a studio space on the top floor of his home. Upon seeing the inside of the house for the first time, she was amazed.

“As you walk in the door, all you could see going up the steps was art,” Thompson said. “And when you got up the steps at the landing, there was art. Every room was like that.” Layers upon layers of images and papers wallpapered the interior of the house.

At first, it was mostly Crite’s work, newspaper and book clippings on display. As he formed relationships with others, he added their art to the walls. Crite’s friends and mentees even recall the space behind the toilet paper holder boasting artwork. “There was no resting place for the eye,” said Thompson.

Members of the Boston Collective and others would frequently visit Crite at his home. “It was a gathering place of ideas,” Tinker said. “Laughter, fun, somebody just dropping by to visit him or whatever. And then it wound up being this whole conversation about whatever was going on in the world.”

One topic that came up regularly was women’s rights. At the time, there was a lot of debate about abortion. “I’m finding this out that as far as women are concerned today,” Crite said in his 1979 Smithsonian interview. “That as long as a woman doesn’t own her own body, none of us is free.” His stance may surprise some, given his Episcopalian background. Both Thompson and Tinker remember Crite as a staunch defender of a woman’s right to choose what to do with her body.

Beyond his philosophical discussions with his friends and mentees, Crite formed relationships with others by opening his home to the general community. Boston activist and mayoral candidate Mel King ran the Rainbow Coalition campaign from the storefront of Crite’s house. Groups of children would visit Crite’s home on field trips and he’d show them how to use his printing press. His house became the stuff of legend in the surrounding area.

There was eventually an effort to turn the Columbus Ave. home into a house museum, but it never fully came to fruition. The house fell into disrepair and Crite and his wife Jackie, whom he married in 1993, had to move. Over the years, some of his work was lost. A few pieces even turned up at a thrift store, Tinker said.

“It’s kind of like a heartbreaking subject for us. You know, that’s the way things work out sometimes. You could put things in place and still, it doesn’t work out the way you want it to.”

Crite never stopped creating artwork, even up until his death in 2007. His friends and mentees recall learning a lot from him over the years. Tinker points out that he knew it was reciprocal.

“You know, working with Mr. Crite, he would always say, you know, people would say, Oh, you have this group of young artists and they’re learning from you. He said, I will also learn from them. You know, we learned from each other.”

While the art world certainly remembers Crite as a prolific artistic pioneer in the 20th century, one could argue that the indelible and enduring parts of Crite’s legacy aren’t the works that he created.

It’s the family and the community that he built for himself in the face of loneliness. It’s the people he taught and mentored. Beyond his art, that part of Crite’s life may be just as important to remember.

“Allan Rohan Crite: Urban Glory“is on view at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum Oct. 23-Jan. 19.”Allan Rohan Crite: Griot of Boston” is on view at the Boston Athenaeum Oct. 23-Jan.24.

اترك تعليقاً