This is the second story in a three-part series on Boston artist Allan Rohan Crite. Read the first story here.

Allan Rohan Crite was a religious man, with values instilled in him by his Episcopalian mother, Annamae Palmer Crite. In his 20s, he developed a keen interest in the similarities and differences between the Episcopal and Catholic churches and began studying the rites of both Christian traditions.

One night, while assisting a priest at St. Bartholomew’s Church in Cambridge, Crite sensed “that behind the altar, there was this presence of the Christ child and the Mother. So I made this drawing trying to interpret that impression,” he described in a 1979 interview with the Smithsonian Institute’s Archives of American Art. The moment in the church catalyzed Crite to make more liturgical works, something he would do throughout his lifetime.

Two Boston institutions, the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum and the Athenaeum, are opening retrospectives devoted to Crite’s work that examine how he captured the range of human experience, from the spiritual to the intimate.

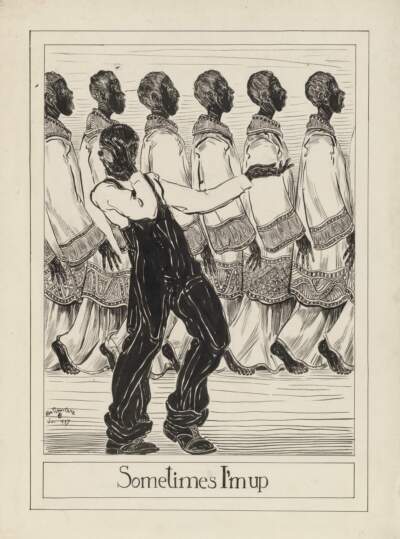

Crite’s devotional side is reflected in some of his paintings and drawings of churches in Boston and Cambridge, and people attending Sunday services. In 1944, he published a book of drawings called “Were You There When They Crucified My Lord,” which interpreted Black American spirituals. The book includes 39 black-and-white artworks.

“I had a feeling that the spirituals were being lost,” Crite said in the Smithsonian interview. “What I did was just try to illustrate a few of them, so that people would get an idea that spirituals are hymns of the church, part of the religious musical literature of the world. That’s why I illustrated them. Almost as an act of preservation.”

For Crite, his liturgical work extended beyond simply depicting religious imagery; he sought to use it as a means to highlight the shared humanity of Black people worldwide.

“Back in those days, the image you got of Africa was man-eating cannibals, wild animals, ‘Tarzan of the Apes,’ and the Rider Haggard story of ‘King Solomon’s Mines’ — that kind of mythology,” he said.

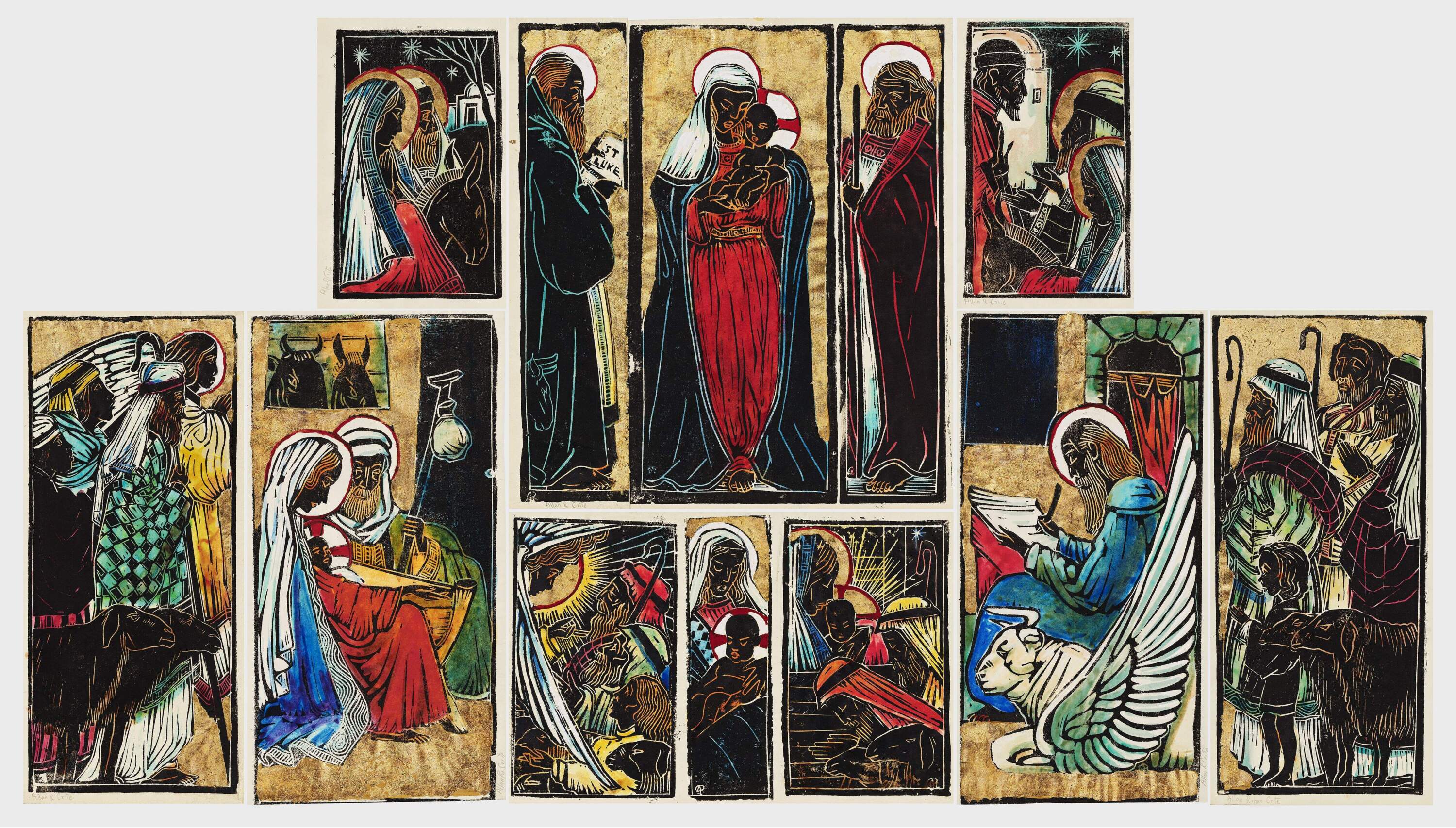

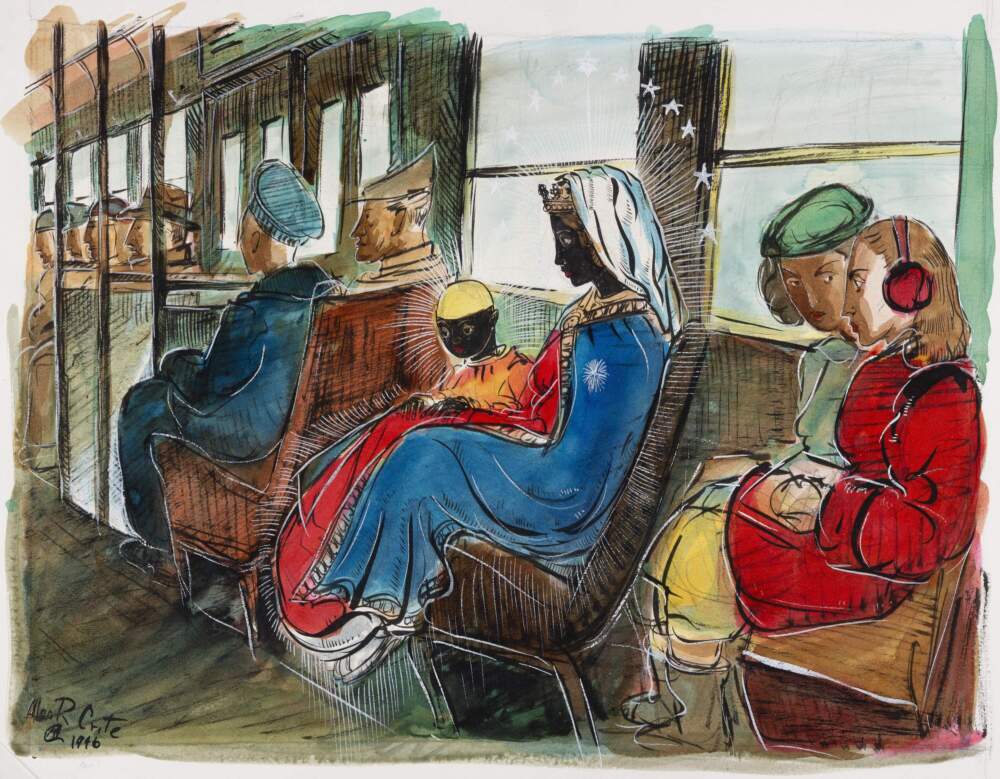

In response, Crite created pieces like his 1946 watercolor “Streetcar Madonna” that reimagined Mary and Jesus as Black. This was a radical step to take in the early half of the 20th century.

“The saints and all of the spiritual folks that you would read about in the Bible, they were all Black in Allan’s work,” said Aukram Burton, an artist and the executive director of the Kentucky Center for African American. Heritage. Burton was a close friend and mentee of Crite. “These Black liturgical paintings were taking place before they were saying ‘Black is beautiful’ in the ’60s.”

Creating Sunday service bulletins for different churches was also part of Crite’s religious oeuvre. In 1955, he got a Multilith offset printing press, which revolutionized how he did his work. Crite drew and used linoleum block prints to create original images that he would then copy and mass print. He estimated that he printed close to 1,200 church bulletins every week.

Johnetta Tinker, another artist who was a friend and mentee of Crite, remembers his process of preparing the bulletins. “He would print them off on his printing press and would have them stacked up,” Tinker said. “He would send them off to different churches, not even here in Boston, but in other places,” like Oregon and Michigan.

The pamphlets and images he created became popular. One 1948 drawing titled “Is It Nothing To You?” juxtaposed Black religious figures against a streetscape, and it became widely recognized within the Episcopalian church circuit. Crite also exhibited his liturgical work at Columbia University, the Boston Public Library and the University of Maine.

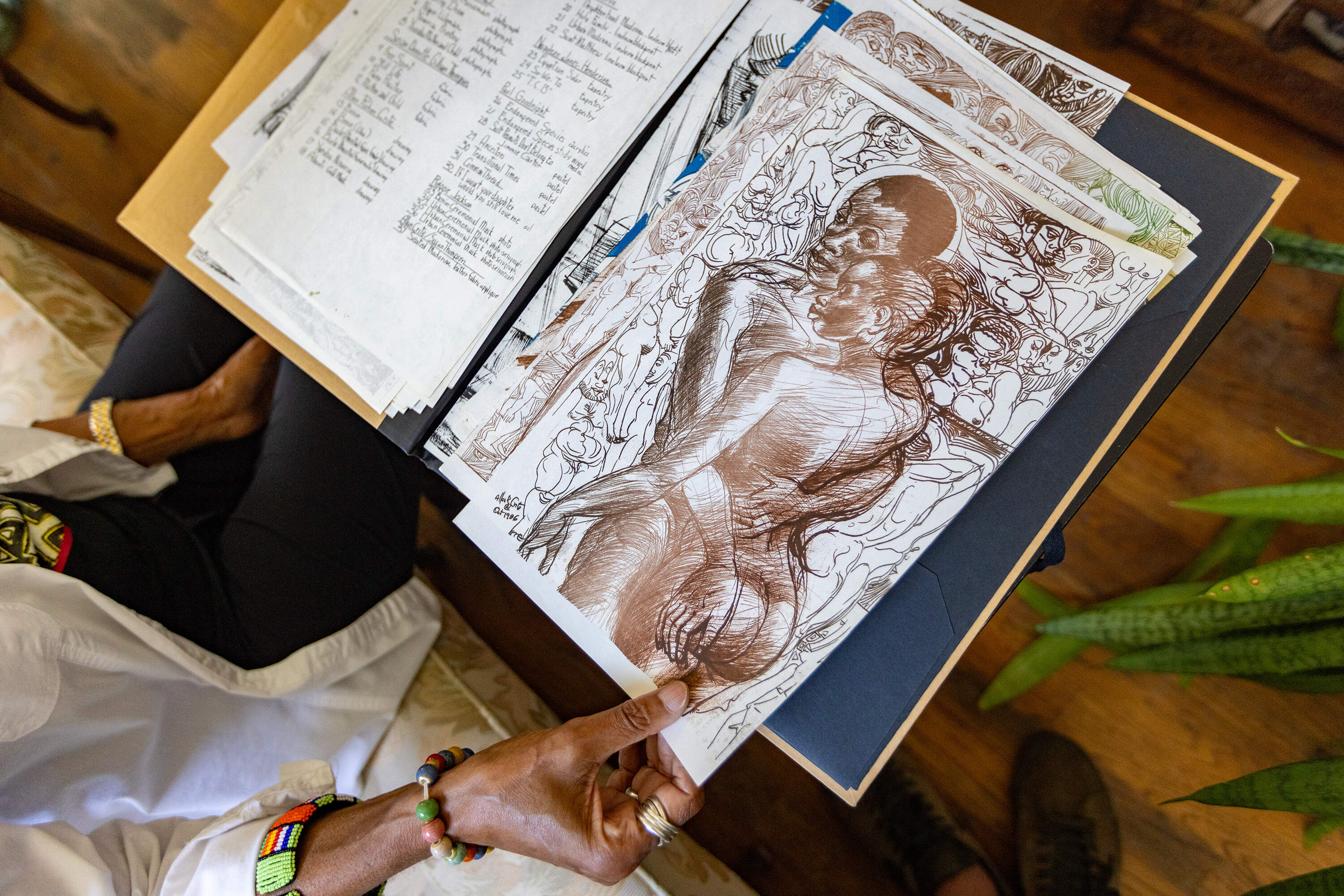

Although Crite was a religious man, he had his criticisms of the church as well. “I’m critical of our sexual position (in the church),” Crite stated in his interview with the Smithsonian. “I’m finding out something else in my examination — that we have a certain element within us, certain basic things, like human sexuality, which is older than any of our cultural institutions; older than the church, older than nations.”

Crite explored the human body and sexuality in many of his later works, but it would be a mistake to simply label it “erotic art,” Tinker said. “He called it human art. This is the human being. This is natural. This is how we’re all conceived, you know? He always talked about Adam and Eve; they were nude.”

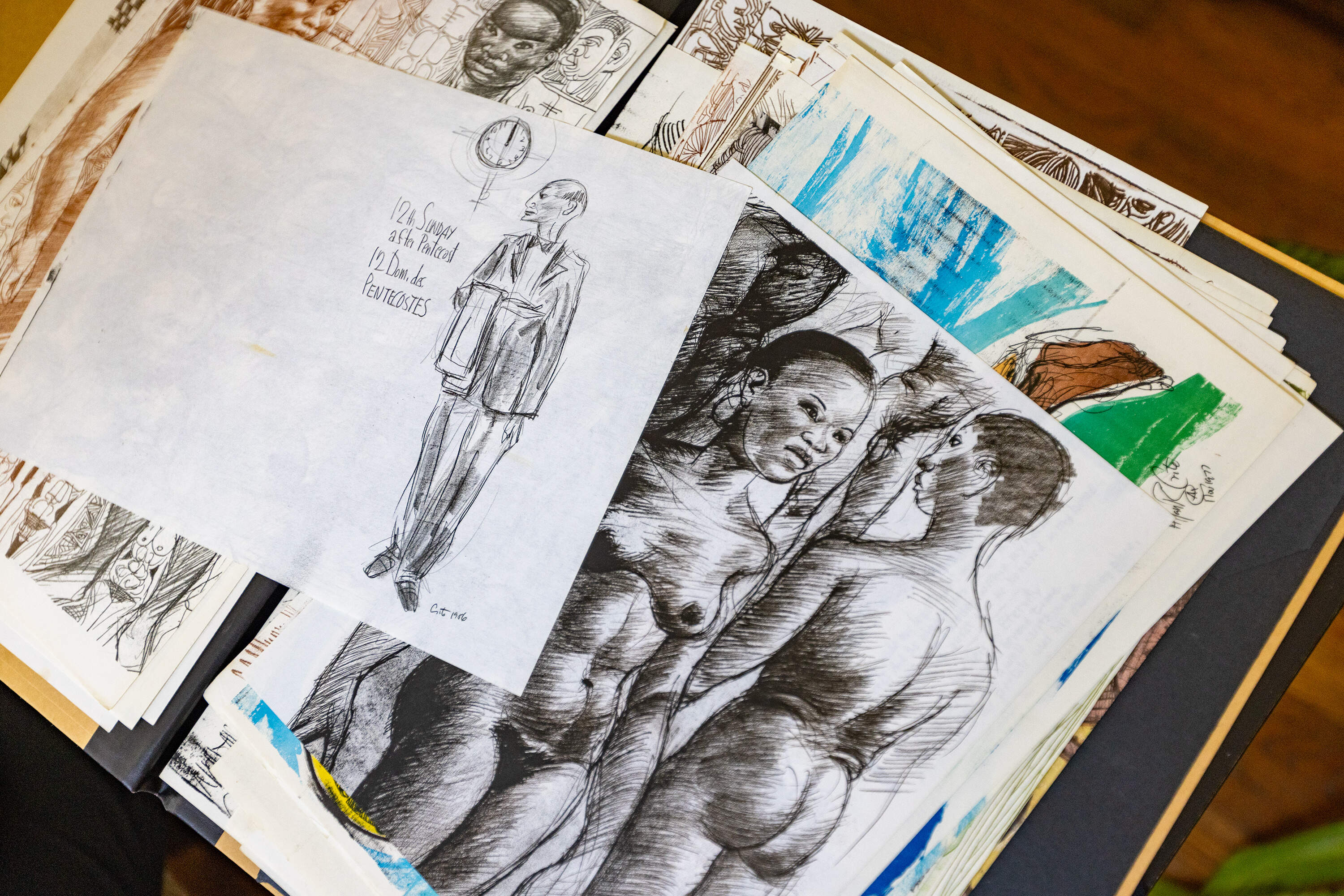

Not everyone appreciated the shift in Crite’s subject matter. Aukram Burton recalled an exhibition at Roxbury Community College in the early 1980s that he, Crite and others participated in.

“Allan had exhibited some nude images and he was asked to take them down. It caused some controversy. Many of us protested,” Burton said. This wasn’t the last time Crite was censored — it would happen again in the 1990s at the University of Massachusetts, Boston.

While some saw these nude works as overly sexual or inappropriate, Crite was merely exploring the foundations of human intimacy. Some works depict mothers giving birth or with their children, unclothed. Others show naked couples together, copulating or simply lying with each other. Crite would visit Boston’s “Combat Zone,” which at the time was essentially the city’s red light district.

“He was really studying the behaviors that emanated out of the red light district,” Burton explained. “He’d go into these little sex stores and see sex objects and toys of human plastic.” Crite viewed these objects as “a fallout from the industrial revolution. The fact that we have been so dehumanized to the point that we have mechanized our own sexuality,” Burton said.

As the subject matter of his work changed, so did his materials. In the early half of the 20th century, Crite used lots of oil paint and watercolor. He eventually shifted to pen and marker. His work became highly stylized and designed sequentially with accompanying words and descriptions, almost like a graphic novel.

“In fact, as he got older, people started to cringe a bit because he was using magic markers and what have you,” Burton said.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum curator Diana Greenwald said that there is a propensity in the art world to value certain mediums above others. “Whenever it’s oil painting versus works on paper, often oil painting sort of wins out. Which, by the way, has all sorts of discriminatory effects because we know that artists of color and women are far more active on works on paper.”

It’s part of the reason whyAllan Rohan Crite: Urban Glory” at the Gardner includes the later works that Crite created and replicated on his press, including some that others may deem “sexually explicit.”

“They’re also incredible works of art. Yes, they’re printed on a home press and yes, he did scotch tape them into a frame,” Greenwald added. “For me, from a scholarly point of view, they are just as, if not more, interesting than the oil paintings.”

Crite’s approach, especially in the late stages of his career, emphasized the democratization of art. It’s why he printed off so many church bulletins throughout his lifetime. It’s also why he gifted so many copies of his works to mentees and friends.

“He made sure that people had a chance to have a piece of his artwork,” said Tinker. “Sometimes we’d have to stop him and say ‘No more, Mr. Crite!’ “

Crite became unconcerned with using the finest materials to create his pieces. What mattered to him was that others got to experience his work. It was a radical way of thinking about the function of art.

“I think that he was so prolific that he was saying, look, it’s not about the medium. It’s about the message,” said Burton. “What he did was revolutionary.”

“Allan Rohan Crite: Urban Glory“is on view at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum from Oct. 23-Jan. 19.”Allan Rohan Crite: Griot of Boston” is on view at the Boston Athenaeum from Oct. 23-Jan. 24.

اترك تعليقاً