Photo-Illustration: Vulture; Photos: Disney, IFC Midnight, Netflix, StudioCanal, Synapse Films, Paramount Pictures, Universal Pictures, Warner Bros.

Almost 100 years ago, Frankenstein (the man, not the monster) declared an ecstatic, revelatory victory over scientific dogma: “It’s alive!” He had imbued life into a body constructed from dead human tissue and, in the process, kick-started a cinematic tradition that nearly every film featuring a mad scientist has been indebted to. In Universal’s Frankenstein, directed by British filmmaker James Whale in 1931, Mary Shelley’s powerhouse gothic text was truncated to a compromised 70-minute version — but every nuance and plot detail the first Frankenstein film left out has been revisited and explored in the 94 years since the bolt-necked monster first woke from his slab and stomped into the world.

When Whale directed his Frankenstein, it had been over 100 years since Shelley published the most widely read version of her “Modern Prometheus” novel (a revision published in 1818). Now, Guillermo del Toro — cinema’s biggest proponent of big-screen fantasy — has completed his two-and-a-half-hour version, an epic adaptation with a blockbuster budget, a stamp of auteurship, and decades spent ruminating on the relevance of Shelley’s text in the modern era. Between these two adaptations, which Frankenstein movies have been the best?

And how do we classify a Frankenstein movie? The novel has been adapted, riffed on, and subverted in hundreds of films from silent shorts to modern teen comedies. Films like Re-Animator, May, and Poor Things can trace their themes and inspiration all the way back to Shelley’s work, but for this list, we’ve chosen a purist criteria: The name Frankenstein (or a clear derivation) is used, referring to either the doctor or his monster. Everything else — including how the movies explore horror, religion, eroticism, enlightenment, gender, and basically any other topic you can think of — is up to the filmmakers. Here are the 20 best Frankenstein movies from nearly a century of them to mark del Toro’s digging into and grappling with Shelley’s text deeper than we’ve ever seen in cinema.

Photo: TriStar Pictures/Everett Collection

While at least Frankenstein films are technically better than Kenneth Branagh’s overwrought adaptation, it is worth talking about because of how it relates to del Toro’s version. Both directors commit to the details of Shelley’s story, inching closer to “official adaptation” status by imitating the basic structure and character roster of the novel. But they both try to go beyond its parameters, taking their story to extremes that Shelley did not. Here, Branagh appropriates the climax of Whale’s Bride of Frankenstein with one of thwarted monstrous companionship, which feels, if not moving, then delirious and kinetic in a way that convincingly drives creator and creation to their doom. Elsewhere, the details lifted from the book suffer in translation: Branagh’s Victor is appropriately arrogant but not adequately tortured; De Niro’s Monster is sensitive and intuitive but drowns in the film’s hurried, hollow second half. Produced by Francis Ford Coppola, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein mirrors the green-lighting of Universal’s 1931 original (i.e., it was designed to follow up a recent Dracula film). The critical failure of this supposedly serious adaptation likely paved the way for del Toro to pool Netflix resources to give it another shot.

Photo: TriStar Pictures/Everett Collection

Across nearly ten years of Stranger Things and its ’80s-nostalgia imitators, it has become clear that media about nerdy suburban kids going on a fantastical adventure are not great for the culture — they are largely inward-looking genre vehicles built out of references and an appeal to an imagined childhood. Fred Dekker and Shane Black’s The Monster Squad lacks the comparatively rigorous craft of E.T. or Gremlins, but pitting children against a crop of Universal monsters like Dracula and Frankenstein’s creation is not without its charm. For the Frankenstein fans, Dekker and Black put a modern spin on the tragic “Little Maria” scene in Whale’s Frankenstein by sweetly pairing the Monster (Tom Noonan) with Phoebe (Ashley Bank), the kid sister of our protagonist, Sean. The film gives the Monster a sincere, innocent friendship that Boris Karloff’s character was denied in Whale’s version — and culminates in a direct reference to E.T.’s farewell scene that is both eye-rollingly cute and unexpectedly moving.

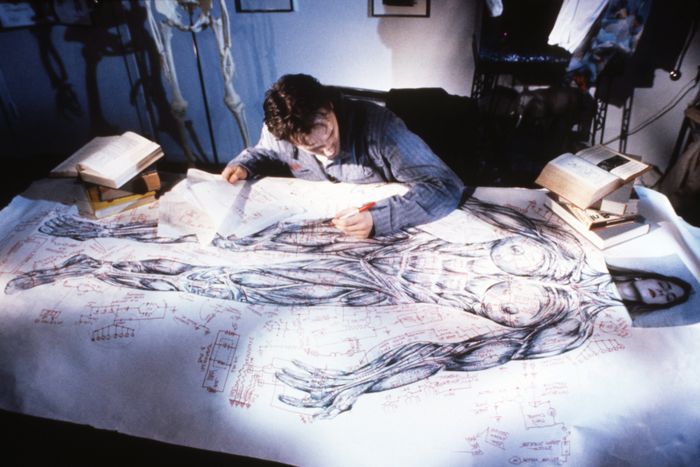

Photo: IFC

Independent horror filmmaker Larry Fessenden began his directing career with No Telling, a low-budget rural riff on Frankenstein featuring heavy relationship drama and animal experimentation. Nearly 30 years later, Fessenden returned to the “Frankenstein complex” with Depraved, a modern take set in New York that begins with the murder of a millennial web designer whose brain is plugged into a stitched-together creation. “Adam” is unaware of the life that was snuffed out to bring him to life. Over its long development period, Depraved suffered a drastic budget reduction, but Fessenden’s threadbare resources are mostly outshone by committed performances from David Call as Henry, our narcissistic creator, and Alex Breaux as Adam. The film honors Shelley’s conception of the Monster with an uncommon degree of sensitivity and notably deploys an array of optical effects to emphasize the experience of Adam’s secondhand eyes taking in the world for the first time.

Photo: Ken Woroner/Netflix

In scale, Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein is the most significant adaptation of the novel in this century. Over two and half hours (it would take you just as long to watch the first two Universal adaptations back to back), del Toro balances adapting the neglected portions of Shelley’s text with a homage to the expressive gothic history of Frankenstein onscreen — all alongside his didactic but sincere commentary on “monsters” being born from historical human cruelty. It doesn’t quite come together. The production design is detailed and tactile (no surprise there), but del Toro has been building toward an official Frankenstein film for so long the material often feels like familiar ground. His Frankenstein quickly declares Victor an unwavering narcissist and denies him the tortured interiority that Shelley gave his narrated testimony in the book. But while Oscar Isaac suffers in that role, Jacob Elordi fares far better, playing the Creature’s appetite for experience with an openhearted vulnerability that borders on recklessness. Del Toro never met a monster he didn’t instantly want to redeem, but the novel’s motifs of revulsion and being eaten alive by the fear of one’s own power are neglected. It’s suitably lengthy, always engaging, but too literal an interpretation to stick.

Photo: Shapiro Glickenhaus/Everett Collection

Splatter and exploitation king Frank Henenlotter established a distinctive (read: shrieking and gooey) style with only a handful of films under his belt, and the provocative title of his Frankenstein riff is probably why interest in this poor-taste B-movie has persisted in the decades since its release. After the untimely death of his fiancée, Elizabeth (Patty Mullen), at the hands of one of his inventions, Jeffrey Franken (a wooden James Lorinz) tries to resurrect her by attaching her severed head to a dozen body parts taken from New York sex workers. Garish, puerile, and button-pushing even before we get to the wicked body horror, Frankenhooker is animated by Jeffrey’s scientific drive and web of anxieties. But after Elizabeth is revived nearly an hour in, it becomes clear Frankenhooker’s fatal flaw is too much Lorinz and way, way too little Mullen.

Photo: Everett Collection

The first of Universal’s “monster rally films,” this crossover of The Wolf Man’s Larry Talbot (Lon Chaney Jr.) and Frankenstein’s monster (Bela Lugosi, who appears three times on this list, never as the same character) delivers the established beats of each one’s horror films in quick succession: the lycanthrope’s desperate pleas to be taken seriously before an unwilling animalistic rampage, and a scientist tempted by impossible breakthroughs whose experiments attract the ire of suspicious villagers. You get what you came for and nothing more. By this point, the potency of the Universal monster movies was clearly slipping, but this is an aptly titled slice of classic horror that, at 73 minutes, is closer in length to an episode of modern TV than a horror movie. It’s a shame they don’t get up to much as a pair in this, as the Wolf Man and Frankenstein make a compelling onscreen duo. They’re more like brethren than rivals, unable to fully control their monstrosity with animal instincts smothering their muted but real humanity.

Photo: Ripley’s Home Video

This obscure Italian art film seldom appears on lists of best Frankenstein movies, because the Monster appears only in the first 40 minutes and the film is far closer to a European arthouse tradition than Universal horror: It’s a series of abstract vignettes showing us snapshots of civilization in cultural and intellectual decline (including frequent Andy Warhol collaborator Viva complaining about her marriage to an impotent Devil). In his segment, Frankenstein’s monster (Bruno Corazzari) roams a room of red Rothko-esque paintings and is overwhelmed by music. As he slowly masters speech with a grating, staccato delivery, we watch him develop a thesis on the human condition in real time — how difficult it is to upset the world order, how freedom can be found only in creativity, and how humankind is inherently embryonic. Director Corazzari embraces the philosophical potential of the Monster’s nascent, hungry mind, culture and morality shaping his consciousness as diagnoses our collective sickness.

Photo: Everett Collection

One of the lesser-known kaiju films from the godfather of Godzilla, Ishirō Honda, Frankenstein Conquers the World starts in WWII, when the Nazis pilfer the ever-beating heart of Frankenstein’s monster and deliver it to Hiroshima scientists. Fifteen years and one atomic bomb later, the Monster has been reincarnated as a feral boy, resistant to radiation and growing at an impossible rate — soon making him gigantic enough to battle Baragon, a horned prehistoric monster with none of Frankenstein’s instinctive humanity. (The Japanese title is Frankenstein vs. Baragon.) The human scientists, including Nick Adams at the tail end of his Hollywood career, add little excitement overall, which is not an uncommon complaint in kaiju movies. But blown up against detailed miniature sets, the Monster’s animalistic physicality and curiosity make for a thoroughly visual upgrade of the cinematic tropes and motifs associated with the character — he is defensive, singled out by his abnormal form, and has to prove his benevolence while trying to survive. With back-to-back fights with Baragon and a gigantic octopus (who arrives with no explanation), Frankenstein’s kinship with King Kong — a simplistic empathy and wrestlerlike physical prowess — has never felt more clear.

Photo: Everett Collection

Britain’s horror-movie legacy owes everything to Hammer Films, whose colorful renditions of classic Gothic characters made the company a household genre name in the mid-20th century. Hammer made seven Frankenstein films, and the best were directed by Terence Fisher; the fifth-best Fisher Frankenstein picture still has a lot to recommend it, including a sharply maniacal Peter Cushing as a fugitive Baron Frankenstein blackmailing a young London couple in his quest to learn the secrets of brain freezing. Twelve years since Cushing first took on the role, Destroyed feels like Fisher’s soft reboot of the series, returning to the nasty characterization and invasive domestic tensions of 1957’s The Curse of Frankenstein. But an uninspired and shallow story — which includes a rape scene demanded by the studio — hampers his attempts to entice us with a chilling and menacing tone.

Photo: Everett Collection

“No, I haven’t given up. I never shall.” So says an older but no less committed Cushing as Baron Frankenstein when pushed by his ambitious young assistant, Simon (Shane Briant), to reveal whether he’s still experimenting at a Victorian asylum. There’s not much separating this and Destroyed in quality but a lot in tone — the sets and colors of Monster From Hell are much more muted, aiding the rich sense of melancholy throughout. Heading up his very own manor of the mentally ill, Frankenstein’s authority is finally challenged as he creates a Neanderthal-like monster with top-of-the-range body parts from murdered inmates (aided by Simon as his hands are no longer good for surgery), and he faces little to no outside pressure or investigation. Even with clearly dwindling resources (Hammer’s golden era was definitely coming to a close), Fisher’s and Cushing’s last Frankenstein is a curious, compelling swan song for the best version of Victor onscreen.

Photo: Everett Collection

The first Universal Frankenstein movie to be produced after Whale’s masterful diptych loses Colin Clive as Henry Frankenstein, jumping ahead to his adult son, Wolf (Basil Rathbone), returning to his ancestral home, where the resentful villagers give him the cold shoulder. Wolf wants to redeem his father’s reputation, but after being led to his debilitated laboratory by the reclusive Ygor (Bela Lugosi), he stokes the flames of his namesake’s dubious ambitions and brings the Monster back to life … again. Closing out the first decade of sound film, Son of Frankenstein has far more ropey dialogue than entrancing atmosphere or a memorable arc for the Monster. Notable for its expressionist interior sets, this sequel is best when Wolf scurries around his newly inherited castle trying to conceal his illegitimate, monstrous family from his clean-cut aristocratic one.

Photo: Everett Collection

On the urging of Roman Polanski, Paul Morrissey (the manager of Andy Warhol’s renowned art studio, the Factory) decided to make a horror film in 3-D, funded by an Italian producer on the proviso that Morrissey make two of them. Flesh for Frankenstein features many of the same cast members as its sister film, Blood for Dracula, including Udo Kier as the title character. Secluded in his mansion with his wife (and sister), Katrin (Monique van Vooren), their two voyeuristic children, and his nebbish assistant, Otto (Arno Jürging), Baron Frankenstein builds a male and female creature to procreate a new species of powerful, pure humans. Aside from these Nazi-ish tendencies, Frankenstein is erotically obsessed with the borders of life and death with wounds and organs as specific sites of fascination; meanwhile, Katrin’s attraction to a lowly, virile farmhand (Joe Dallesandro) jeopardizes the sanctity of the experiments. Morrissey explodes the comparatively respectable conventions of prior Frankenstein adaptations by embracing the deranged erotic and fascist implications of building and breeding new life. The vigor and discomfort coursing through this ’70s oddity make it compelling despite many rough patches.

Photo: Everett Collection

The behind-the-scenes drama of this comedy-horror film sounds a lot more stressful and tense than anything in the film (multiple actors hated the material, played hooky from set, and disavowed the final product). Credit goes to director Charles Barton for steering a chaotic ship, as this attempt to boost the commercial appeal of Abbott, Costello and the Universal horror roster finds the right balance between a solid B-movie plot (Bela Lugosi’s Dracula wants to restore Frankenstein to full power with Costello’s obedient brain) and quick-witted extended routines between the high-pitched Costello and the ever-frustrated Abbott. The escalating, hysterical hijinks are grounded in convincing dramatic stakes, and only our comic heroes are allowed to be funny, as the monster actors dutifully honor the hammy seriousness of their characters. In the final set piece, a Dracula vs. Wolf Man fight is shunted to the background for the main event: two screaming comedians chased by a massive, groaning monster, deploying practical jokes and tricks to keep their pursuer at bay. It’s a cynical but ultimately winning attempt to get multiple Universal talents to share the same sandbox, play nice, and boost their image.

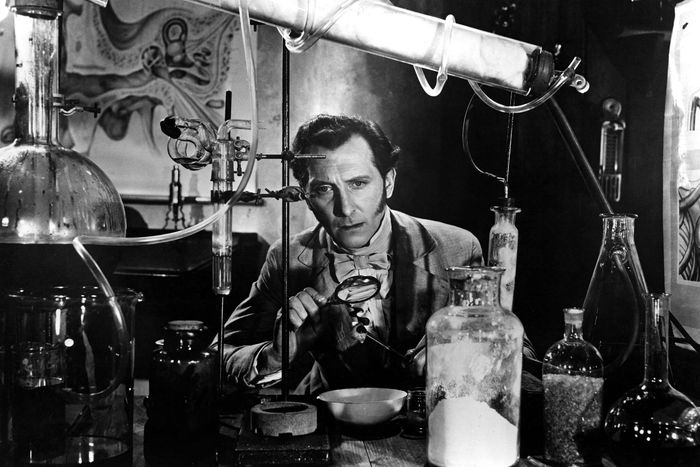

Photo: Everett Collection

Hammer Films graduated to bankable commercial success after its first color film, which gave a lurid, grisly update to the Frankenstein mythos for the generation that came after the audience for Universal’s early run. The reason The Curse of Frankenstein has an original story is more litigious than creative: Shelley’s book was public domain, but Universal’s cinematic (and arguably definitive) version of the character was copyrighted. Here, Victor Frankenstein (Peter Cushing) inherits his estate young, befriends his affable tutor Paul Krempe (Robert Urquhart), and alienates his cousin and fiancée, Elizabeth (Hazel Court), as he murders and manipulates his way to creating a living, breathing Monster (an early performance by Christopher Lee). Director Terence Fisher puts together a robust, suspenseful Gothic film that borrows from Poe as well as Shelley; apart from featuring vibrant colors and salacious desire (a Hammer staple), Curse of Frankenstein distinguishes itself by focusing on the typically unfriendly domestic rhythms of Frankenstein as a European aristocrat. Victor seems to dislike human beings — women especially — and disguises his overzealous experiments by gesturing to his noble authority and singular intellect that the neglected Elizabeth must reluctantly accept. It’s a cold, ugly take on Frankenstein’s mad genius.

Photo: Everett Collection

From a purist’s point of view, it’s unclear how much Victor Erice’s glacial drama about losing childhood innocence in Spain’s Franco regime can be considered “a Frankenstein film.” Whale’s Frankenstein, dubbed in Spanish, features heavily in the opening, in which the earlier film is toured to a quiet village and watched avidly by a crowd including 6-year-old Ana (Ana Torrent), but the characters are reacting to the Frankenstein story far more than they could be called active participants in it. That said, an appearance of Frankenstein’s monster in this movie’s climax — in which Ana has run away from her repressed family — directly invokes the murder of Little Maria in Whale’s film. Whether the Monster is part of Ana’s imagination or not, the scene carries a fragile, haunting power suggesting the only person capable of rescuing Ana from the pervasive mystery and misery of her home life belongs to the supernatural, outside the punishing borders of Franco’s Spain. Erice contrasts the clear moral instruction of conservative Frankenstein interpretations — that we must resist the temptation to undermine God’s authority — with a story of adults failing to give their children clarity and compassion in a world of suffering.

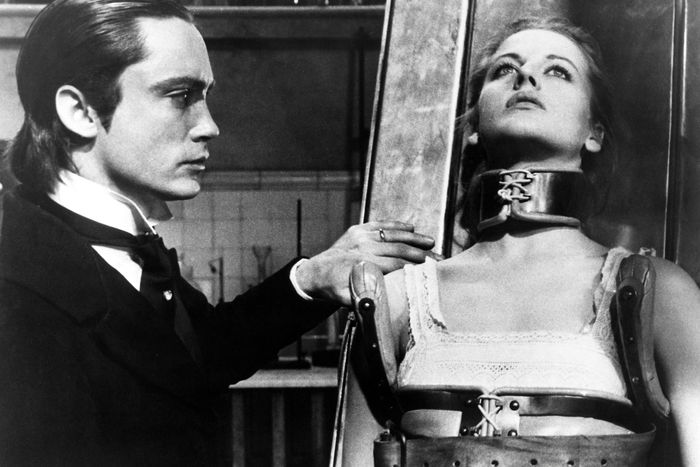

Photo: 20th Century Fox/Everett Collection

This is the fourth Hammer Frankenstein film but only the third directed by Fisher. After nine years away from the baron’s experiments, Fisher returns for a gut-punching tale of undesirable outsiders, execution anxiety, and gender-bent possession. As he works away in an anonymous town, Baron Frankenstein’s authoritarian scientific ambition results in catastrophe for two young villagers: his assistant, Hans (Robert Morris), the son of a notorious local murderer; and the innkeeper’s daughter, Christina (Susan Denberg), who falls for Hans after years of living in shame with her facial deformities. When both young people meet their end, the baron saves Christina by putting Hans’s brain in her body, uniting their blurred identities in a joint thirst for revenge, creating a Gothic avenger who hunts down the aristocratic ruffians who ruined their happiness. Frankenstein Created Women is a notably visceral and haunted chapter in the canon, urgently and creatively exploring Frankenstein’s lack of control over his creation. Here, the scars of cruel violence linger metaphysically, even after death and consciousness has been transferred to a body of a different sex. Christina becomes a being of pure, violent will.

Photo: Everett Collection

The second Hammer Frankenstein includes some of the studio’s favored thrifty production strategies — such as reusing sets from the recently completed Christopher Lee–starring Dracula. But this was the first of three Fisher Frankenstein films to substitute the iconic Monster for an equivalent and ill-fated experiment; in this case, a paralyzed hospital assistant, Karl (Oscar Quitak), who agrees to have his brain transplanted into an able body (Michael Gwynn). Revenge softens some of the baron’s colder mannerisms into a more playful performance from Cushing; after escaping the gallows, he hides his true identity and takes work at a hospital for the poor to access a supply of body parts. His assistant, Hans (Francis Matthews), is a willing protégé who’s curious about the transgressive work, and their combined apathy to suffering only makes the distress of Karl’s brief post-experiment life more upsetting.

Photo: Everett Collection

Mel Brooks’s best comedy shares many similarities with his other revered films: a strong grip of genre beats, a nonstop barrage of gags yanking us forward, and an eagerness to give every performer a chance to comedically shine. (Marty Feldman! Teri Garr! Cloris Leachman! Madeline Kahn!) What edges Young Frankenstein near to the top of our list is how rich and subversive it is as a Frankenstein film. Brooks builds a rich pastiche of the Universal Frankenstein movies — stagey but attractive sets, sharp black-and-white cinematography, and whole scenes cribbed from these earlier adaptations — and injects it with a vein of crass hysteria that underlines how the iconic ’30s movies explored gothic horror with highly strung, heightened characters. Gene Wilder parodies the Dr. Frankenstein archetype with feverish intensity, taking the anxiety seen in prior iterations of the character and making it absurd, while Brooks takes a gamble by letting the Monster be funny. Seeing Peter Boyle mug for the camera with a smarmy grin is as compelling as any serious approach to the Monster’s humanity.

Photo: Everett Collection

The first major Frankenstein film liberally adapts its source material, but in lieu of staging the novel as written, director Whale leans into expressionistic production design and gothic spectacle. The resulting 70-minute film remains the definitive cinematic vision (or revision) of Frankenstein the man creating Frankenstein the Monster. Gone is the Creature’s sophisticated consciousness, his months spent in solitude, his intimate revenge plot. He has been replaced by a golem (the inimitable Karloff) in a singular, instantly recognizable redesign brought to life in a hilltop castle by an intensely cinematic asset — lightning. Whale and Karloff’s Monster may lack the articulate perspective we access in the incredible midsection of Shelley’s novel, but the Monster’s sullen, imposing presence complements the animated, maniacal energy of his creator, Henry Frankenstein (Colin Clive). Outside of the Monster’s ill-fated voyage into the human world (and its comparatively fragile bodies), Frankenstein is notable for underlining the thorny familial themes inherent in a young scientist “birthing” a child outside the traditional means. After Henry abandons his Monster and returns to his fiancée, his father (Frederick Kerr) expresses his anticipation for a Frankenstein heir, prompting a close-up of Henry thinking anxious, impure thoughts about the abhorrent son he has already brought into the world.

Photo: Everett Collection

Whale’s sequel touches on everything a Frankenstein movie ought to. Indeed, no film of the past 90 years has given a more exciting and haunting take on this mythos. We have the scientist’s temptation to triumph over death fused with his petrifying anxiety; episodes of the Monster discovering the extent of society’s capacity for both compassion and cruelty; and a queer subtext about a controlling scientist pulling Dr. Frankenstein away from his happy hetero marriage toward his preferred type of procreation — in this case, a female equivalent for Frankenstein’s monster to reproduce with. On top of the rich story (packed into a brisk 75 minutes), Bride is a classic feast for the senses, filled with the sound of crackling, tempestuous electricity and strikingly lit faces, which have the greatest impact in the extended life-giving climax when the Bride (Elsa Lanchester, who also plays Shelley in a prologue) awakens in a world she immediately, viscerally detests. Bursting at the seams with pathos and hysteria, Bride of Frankenstein honors the source material with refreshing originality in an imaginative expansion of Shelley’s novel that has proved unsurpassable.

Source link

اترك تعليقاً