To have eight minutes of jokes also function as the setup for one big fat switcheroo is rare, impressive, and difficult to orchestrate.

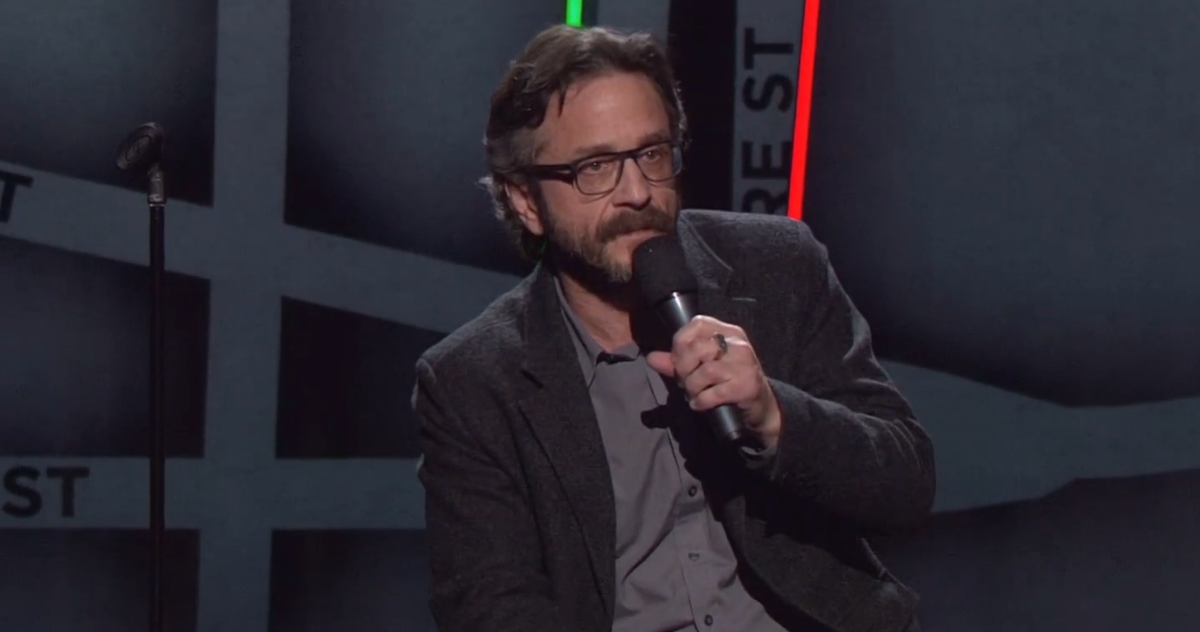

Photo: Comedy Central

Marc Maron’s January 2010 set on John Oliver’s New York Stand-Up Show runs over 14 minutes, but that’s part of what makes it great. Maron holds the audience’s attention the whole time, fanning their energy into a crescendo finish with a single story as long as three The Tonight Show sets. The length allows Maron to fully explore an incident from his nuanced, conflicted point of view. “The industry wishes stand-ups were like pro wrestlers, whose shtick can be explained by a single trait like ‘Macho Man Savage’ or ‘Hillbilly Jim,’” comedian and author Mike Bridenstine once told me. “If it were up to them, comics would be literally named the Redneck, the Nerdy Girl, and the Loud Italian.” Maron’s work flies in the opposite direction of this. Each bit is a testament to his career-long insistence that the richest comedy comes from the complex, messy, multifaceted perspective of a real person. It took him years to master the skills that enabled him to make this approach work, and they all coalesce to make “Almost Died on a Plane” exemplary. Watch it now.

Maron gets his first laugh in 11 seconds and nine words when he tells the audience he is judging them. “I hate when people say, ‘Hey, don’t judge,’” he continues, “’cause I think, You don’t take away my hobbies.” It earns a laugh 20 seconds in and allows Maron to sit down without wasting the audience’s time. Working from the stool, which is one of Maron’s signature techniques, pulls the audience in and makes them focus on the comic’s face and words. For a subtler act, it’s an effective way to reset the energy in a room that may have just seen Chris Rock practice his Oscar material or Bobby Lee take all his clothes off and plop down in an audience member’s lap. Sitting down also happens to be what you do when you almost die on an airplane — or, as Maron soon corrects himself, “in my mind, I almost died on an airplane.” His decision to sit immediately pays off; it’s instantly easier to imagine him in the scene he’s setting up, and the audience’s increased attention allows him to draw a laugh with just a facial expression at the 1:11 mark.

Maron explains that he was an awful flier until he made a vow to let go of what he can’t control. But when his pilot announces there’s turbulence on the way to Cleveland but thinks he will miss it, Maron’s vow goes out the window. “What’s with his attitude? Why’s he so cocky? Is he a hot dogger? Is he gambling with us?” Maron frets before managing to shove his reawakened fear aside, put on headphones, and watch Woodstock. Around the three-minute mark, he’s barely begun his story, and no one has come close to almost dying on a plane yet. But despite all conventional stand-up wisdom, his audience is hanging onto every word.

Maron makes a Joe Cocker face as he recounts lightning filling the sky while “With a Little Help From My Friends” plays through his headphones; then he imitates the passenger behind him screaming, “Oh God! No!” nor the plane plummets towards the earth. He describes asking himself, in the thick of the storm, “Do I want to die to this song?” This earns his first of many applause breaks at 4:25. His thorough work setting the scene in the first four minutes pays off with more applause 12 seconds later when he recounts himself wondering if he should make a “death playlist,” and then another ovation at 4:52 when he acts out picking the soundtrack to his own heart attack.

At 5:08, Maron reveals he wished his girlfriend were there in the moment — “to die with me!” As the audience howls, he adds that this is “actually a functional metaphor for all my adult relationships.” He does like to judge people, it turns out, and especially himself. “Plane’s crashing. Get onboard,” he deadpans in a pitch to a potential lover. At 5:31, he informs the crowd, “You don’t choose your scream.” He reports with pride at 6:10 that his initial exclamation during the storm was a bassy, aggressive “Oh, come on!” The crowd applauds for 13 seconds both at the intense, almost Chris Farley–esque yell itself and the absurdity of Maron’s desire to be a manly coward.

Maron receives another ovation after he reveals the second thing out of his mouth: “Are you fucking kidding me?” Dropping your first F-bomb this late in a previously clean set gives it a lot of impact, and Maron deploys it surgically. After he confesses that his third exclamation was, “Jesus, don’t like this!,” Maron adds, “And he’s not even my guy!” After telling the crowd that his God is the true God, but “live the lie you want,” he gets another applause break at 7:07, then another at 7:17 for imagining shouting out, “Yahweh, no!”

Then Maron pulls off a masterful misdirection. At the top of his set, he had specified that this was a story of the time he almost died “in his mind.” Eight minutes into the bit, he describes asking the passenger next to him, after the danger has passed, if the whole plane was screaming as well. “No, just you two guys,” she tells him. Those five words pull the rug out from under Maron’s entire story and earn a loud, ten-second applause break. Every joke relies on some level of misdirection, but the payoff is usually immediate. To have eight minutes of jokes also function as the setup for one big fat switcheroo is rare, impressive, and difficult to orchestrate.

At 11:56, we get one of the most distinguishing features of Maron’s comedy: a willingness to reveal intimate and uncomfortable details of his life. He tells the crowd that he celebrated his survival by masturbating in his hotel room — not to thoughts of sex, but just to “being alive” — and in response, the audience claps and cheers for 15 seconds. Most comedians would have ended the bit there, happy with their transgressive triumph, but Maron pushes further. After imploring the audience not to judge him (after beginning the set by telling them h was judging tell), he adds that he “finished on the floor.” He then acts out his shameful confession to his girlfriend over the phone. Why did he finish that way? “Because that’s what freedom feels like sometimes,” explains Maron. “And then I started humming the national anthem,” he ends the piece to a thunderous reception.

Maron’s persona could never be reduced to a WWE-style moniker. Over his decades-long career, his style has evolved from the brash long-haired firebrand who performed with Sam Kinison and Bill Hicks to the multifaceted talent he is today. In the black-box theaters, hipster bars, and comic-book-store back rooms that made up the ’00s LA alternative scene, he learned to take risks with his subject matter and open himself up beyond what most audiences expect. At the Comedy Store, he learned to tighten that material and sell it hard enough that random tourists laughed just as hard as the alt-comedy scene’s superfans. “Almost Died on a Plane” displays the results: an epic bit that only Maron could conceive or perform and a strong argument that despite what may make an act easier to sell, comedians are as complex and conflicted as any human being, and the more they let that inform their work, the richer and more compelling that work will be.

See All

اترك تعليقاً